The Growth of Coffee, Quinoa & Cronuts

Food trends have always grown and shifted, but never this quickly.

It’s wholly new that a spike in demand for a niche grain on one continent might so rapidly escalate its price on another. And as the internet pulls the world ever-closer together, this phenomenon seems unlikely to slow or disappear anytime soon.

I spent some time in Vietnam last year, and one of my first lunches in the country — ultimately my favorite — was from a small hole-in-the-wall in Ho Chi Minh City, recommended to me by the owner of a nearby shop. The dish is called “cơm tấm,” and it’s simple: just rice, grilled pork, a fried egg, thinly-sliced cucumbers and tomatoes, a few julienned pickeled vegetables, and chili-fish sauce to drizzle over it all.

I mentioned the dish to a woman at my hotel, and she told me how the name, “cơm tấm,” literally means “broken rice.” The moniker refers to the tiny rice kernels comprising the dish, in contrast to the longer, complete grains one usually encounters.

She explained how broken rice had once been considered a dish for the poor. The broken grains were the run-off, the chaff, left over from processing the more highly-prized long grains. Broken rice was less expensive to purchase, and for this reason was the primary form of rice she consumed as a child with her family.

I personally enjoyed this novel type of rice. The texture of the small grains resembled something like couscous, and readily absorbed the flavors of foods around them. I also learned the rice cooks more quickly than its long-grain cousin.

And I learned I’m not the only one enjoying broken rice for reasons other than cost today. The hotel manager explained how its popularity had recently boomed in Vietnam, how it’s now in fact more expensive to purchase than its long-grain counterpart.

When I asked if this bothered her family, the hotel manager only laughed and shrugged, and said they’d simply begun buying the long-grain rice instead. Her family, at least, seemed unperturbed by shifting trends in food fashion.

The story about broken rice in Vietnam reminded me of another food trend from another part of the world: quinoa.

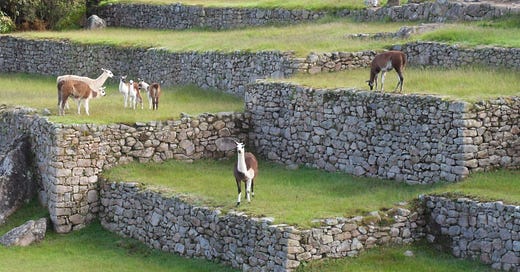

Stories originally reported that the rise of quinoa consumption in the US led prices of the commodity to skyrocket in Peru, where the grain had for many generations been grown and eaten by low-income families. There was a certain dark humor in this, to think that just as wealthy, health-conscious Los Angelenos were scooping heaps of quinoa onto their salads, poor families high in the Andes were losing access to a cultural staple they’d relied upon for generations.

But this tale isn’t quite right. Subsequent research by economists in fact found the global quinoa boom both raised incomes for Peruvian farmers, and did nothing to decrease consumption of the crop there.

As NPR reported in their coverage of a study analyzing the data,

“The working paper does not mince words: ‘The claim that rising quinoa prices were hurting those who had traditionally produced and consumed it [is] patently false.’

‘It's really a happy story,’ [study author] Seth Gitter tells us. ‘The poorest people got the gains.’ Rich people had to spend a bit more, and did.”

Nevertheless, the “quinoa story” hints at a grander observation about our ever-more-globalized and interconnected world. It’s a wholly new phenomenon that a spike in demand for niche grains on one continent might so rapidly rocket its price on another. And as the internet pulls the world ever-closer together — potentially homogenizing and “flattening” great chunks of global culture, as Kyle Chayka wrote in Filterworld earlier this year — this phenomenon seems unlikely to slow or disappear anytime soon.

Quinoa and broken rice aren’t the only “peasant” foods to have spontaneously gained in prestige and price, either. As David Foster Wallace wrote in his classic “Consider the Lobster,”

“Up until sometime in the 1800s… lobster was literally low-class food, eaten only by the poor and institutionalized. Even in the harsh penal environment of early America, some colonies had laws against feeding lobsters to inmates more than once a week because it was thought to be cruel and unusual, like making people eat rats. One reason for their low status was how plentiful lobsters were in old New England. "Unbelievable abundance" is how one source describes the situation, including accounts of Plymouth pilgrims wading out and capturing all they wanted by hand, and of early Boston's seashore being littered with lobsters after hard storms — these latter were treated as a smelly nuisance and ground up for fertilizer.”

But the transition of lowly lobster to fancy feast took the better part of half a century. And the spread of interest in coffee across Europe in the 16th century took even longer. Coffee apparently reached Hungary and then Vienna in the years 1526-29, but it took nearly sixty years before Venetian botanist-physician Prospero Alpini published a description of the coffee plant. And more than one hundred years passed before the first coffee shop opened in Venice.

The idea and substance of coffee arrived in Europe via the physical bodies and sailing ships of the Ottoman Armies. And four hundred years later, lobster received help clawing its way to popularity across the United States via a burgeoning rail network. But it still took decades for the lobster trend to catch on, and for the price of the food to move from that of “cat snacks” to “fine sirloin.”

And now we have the internet to spark demand for these trends, and fast-moving cargo ships and planes to transport the foods supplying them. Relative to lobster’s slow rise in popularity, and the even-slower spread of coffee across Europe, quinoa, avocado toast, and various other foods of the 21st century have closed gaps of class and geography at astonishing speed.

Just look at per capita avocado consumption in the United States, which grew a stunning 450% over the two decades beginning the year 2000:

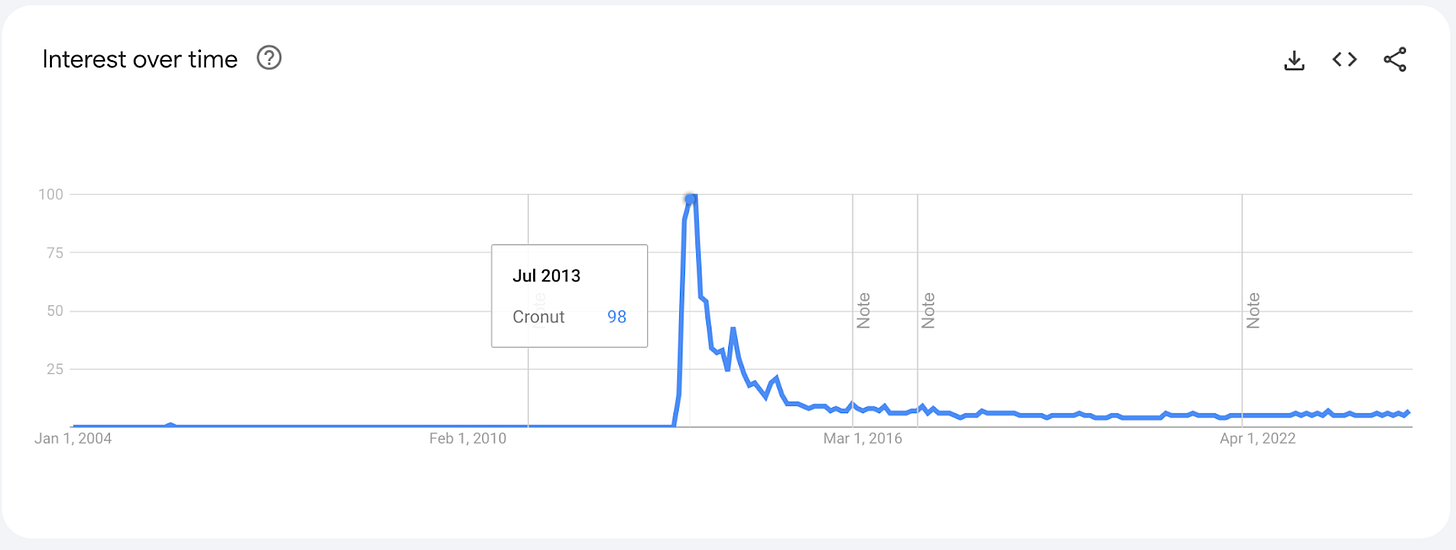

And let’s not forget the Cronut — which, notably, most of us have likely forgotten. When Food Network celebrated the pastry’s tenth anniversary last year, it highlighted social media’s role in its rapid rise to fame:

“It was named one of TIME’s top inventions of 2013, became a Harvard Business School case study and even got the NFT treatment. But perhaps most importantly, it ushered in an era of ’grammable food: over-the-top milkshakes, crazy burgers and, of course, no shortage of hybrid pastries seeking to be the ‘next Cronut.’”

I sought far and wide for research validating the increase in speed of global food trends like these, and failed to find much. (If you know of any, please send my way!)

But it seems clear that the speed at which trends like these can spread across continents and classes is yet another feature of our increasingly-interconnected global world. And that things will only move faster from here.

Song of the Week: Immortal Technique — Peruvian Cocaine. Immortal Technique was born in a military hospital in Lima, and his family immigrated to Harlem, New York to escape the Peruvian Civil War when he was two.

It definitely took me sixty years to learn to love coffee. And shit, I'm still working on lobster. I mean from a chef's perspective, that shit sucks to make, getting that tail broken open and easy to eat, fuck! No wonder they didn't appreciate it. Spend more calories preparing it than you get from eating it.