I considered making this post, the first of the new year, a light, fun one — but Gaza has been on my mind since, well, at least October. And I’ve been working on the essay that will comprise this and the next few posts for quite some time, so here we are.

(That said, it doesn’t feel right to not at least say something resembling Happy New Year. This will be the first full year of The Web and The World, and I’m happy to have you with me for it. Thank you to readers who’ve been along for the ride so far :) I hope 2024 brings good things, dark as they may look for so many right now.)

I’ll be reading portions of this aloud on our podcast sometime in the next week or two as well, so subscribe and stay tuned there if you’d rather listen. But I’ll be writing much more than will be on the podcast — I tried reading the whole thing aloud and it just came out, well, weird — so stay here if you’d like to learn more.

And I encourage you, please do learn more, whether here or elsewhere. I care a lot about this stuff — like, “sleep has been hard the past few months” level of care. And if you’re American, know that our country wields tremendous power, and I’d argue responsibility, in negotiating this conflict to help create both long- and short-term health and freedom for Palestinians.

As some of you know, I’ve been fortunate enough to visit Gaza, twice — first in 2015, and again in 2017 — as a startup mentor with Gaza Sky Geeks, Gaza’s first, and I think only, tech accelerator. I’d hoped to visit again in 2020, but we all know what happened then. And I thought about visiting this coming summer, in 2024, but I’m not optimistic that will happen, either.

I’ve cared deeply about Gaza since my first visit over eight years ago. It’s hard not to go there and meet the people I met — to see such an amazing well of talent, ambition, hope, optimism, generosity and more — and be inspired, and humbled; to wonder how that well hadn’t run dry years earlier despite so many ways it could, and you'd think, should. And it’s hard not to come away wanting to tell everyone you know to please, pay attention to Gaza — because there are people living there, lovely people like you and me, and no one’s listening to them.

What follows are stories from my own time in Gaza and the West Bank, and stories of friends and acquaintances I’ve met during those visits and since. What I’d like to show is what it was like to visit Gaza before all this began — what it’s like there when bombs aren’t falling. I first wrote this essay in 2017, after my second visit, and have edited and added to it off-and-on since. I’m grateful to finally get it out into the world.

I have a fear that once this war stops, or drags on long enough — once the US political election gains steam, and social media influencers find some new cause célèbre — international attention will move away from Gaza. And what comes next there is anyone’s guess. What I hope to do is convince you that even if it were possible to return Gaza (and the West Bank, too) to the status quo that predated the awful October 7th attack, it would still be horrible for Palestinians. If there’s anything I hope the past few months have shown the world — and they’ve been awful — it’s that the status quo in Palestine should never have been sustained in the first place.

President Obama talked about the conflict, and also America’s role in it, on Pod Save America recently. Of particular interest here, he said:

“You can pretend to speak the truth. You can speak one side of the truth…. but that won’t solve the problem. And so if you want to solve the problem, then you have to take in the WHOLE truth. And you then have to admit nobody’s hands are clean, that all of us are complicit to some degree.”

So I’d like to acknowledge that what I’m writing here is one side of the truth — my own. I’ve thought long and hard about what I’m writing here, some of it for nearly a decade. Whether or not this resonates with you, or makes you uncomfortable, I ask you to take it, and weigh it, and consider the truths of others around this as well.

Because I do believe we have to take in a great many sides and truths and stories if there’s ever to be any end to this that looks like peace, and fairness, and freedom.

Thinking Concretely

Before I get into what it was like to visit years before the current conflict, I’d like to share what it feels like right now to have been to Gaza — to know people and have formed memories there, to hope one day to revisit a place that will never again look like the one you left.

As I said, I went to Gaza to mentor tech startups with Gaza Sky Geeks. It is — or was, I honestly don’t know what happens when this ends — an amazing nonprofit that brought in young, talented Gazans, gave them office space and internet, food and fresh water, and above all hope, optimism, and a semblance of opportunity. All of which have been incredibly hard to come by in Gaza for at least as long as I’ve known the place.

Gaza Sky Geeks brought in mentors from outside the region to give talks and advise the tech product teams, which is how I was able to visit. I’m immensely grateful for the opportunity, especially now: it’s no exaggeration to say my time in Gaza impacted me more profoundly than many other things I have experienced.

Days after October 7th, when Israel began bombing, someone at Gaza Sky Geeks posted a photograph of the outside of the office to Instagram Stories. The office sits a few floors up a tall building, and the photograph only showed its facade. The building still stood, but nearly all the office windows had been blown out.

Now this is a relatively small thing. Relative to the death toll in Gaza from this conflict (over 21,000 as I type), relative to the many more injured, relative to the roughly 85% of Gazans either temporarily or permanently displaced. Relative too, of course, to the pain, heartbreak, fear and anger caused by those Hamas killed and harmed and kidnapped from Israel, and the global rise in antisemitism that has flowed downhill from Israel’s response to the attacks.

Take away the relative qualifier there for a moment though. Imagine you run a small business, and one day you show up to find nearly all the windows smashed out. You’ll want to fix them before people really start working again — what about weather, and birds, and break-ins? And then how do you fix them? Everything is harder in Gaza — importing windows, buying windows, importing whatever adhesive you need to install windows, finding window installers… and on and on.

Even if that office still stands after the war stops, I wonder how long those windows will remain broken. My last time in Gaza, in 2017, it was hard not to see rubble, left over from the last big war, a full three years earlier. And that war was much, much smaller than this one.

More than 2,000 people were killed in that conflict in 2014, and nearly ten times that many have been killed the past three months alone. That’s almost 1% of the entire population of Gaza prior to October 7th — proportionate destruction relative to the US population would mean the deaths of 3.3 million people. This sounds like an unfathomably large number of deaths, and it should.

Numbers like this are hard to truly grasp, so let’s consider contacts in your phone, or Instagram followers, or Facebook friends. Scroll through your contacts until you get to 100, and realize that if you’d lived in Gaza all your life, at least one of those people would likely have been killed in the past three months. Two or three would have been injured; nearly everyone you know would have lost someone they know, and probably many people. More than 85 out of every 100 people you know would have had to flee their homes, and many would have lost those homes forever.

It’s unpleasant, but try to think of a time when a sudden tragedy reverberated through a community you’ve belonged to — an unexpected death, say. The community might have been your school, your neighborhood, your synagogue or church or even Burning Man camp. Anything decently tight-knit.

How did that feel, for the community? How did information move throughout it — how did people talk about the victims? How long did the news of the tragedy circulate — was it weeks, or months, or more?

Would you say that tragedy was shocking? We have certain terms — we say that a shock spread through a community, or maybe it echoed, reverberated, or resounded — to emphasize the ability of tragic or otherwise remarkable news to spread through a social network, to fundamentally shift the standings of those within it.

So we use words like shock and reverberate and echo and resound to describe how tragedies we’re familiar with, if only peripherally, can affect a community. But how are we supposed to describe the impact of what’s happening in Palestine now? There’s a reason a special Hebrew word, sho’ah (שואה), exists to refer explicitly to the Holocaust, and a special Arabic word, nakba (النكبة), to refer explicitly to the displacement of Palestinians in 1948. These things are too big, too reverberate-y and shocking and, well, traumatic, to depend on the use of any ordinary word.

And both these words mean roughly the same thing: “catastrophe.” Each of them took place nearly 80 years ago, and their memories have been passed down, like sour and wicked heirlooms, from one generation to the next.

How many generations of Palestinians will look back bitterly at this tragedy? What collective term will coalesce to refer to it 10, or 20, or 80 years from now?

What it’s like to know Someone in Gaza

I’d like to share one story about a Gazan I know who’s there right now, and then I’ll wrap up this post for this week. I’ll be posting the essay in serialized form over the next week or two — like I said, it’s long :)

When I first visited Gaza, I met a woman I’ll call Dina. My memory of her — I haven’t seen her in at least six years — is of a rather shy, kind, but also smart and driven woman. We hadn’t talked for a long time, but last spring she reached out seeking advice on fundraising strategies for a startup video game she’d begun with a cofounder outside Gaza.

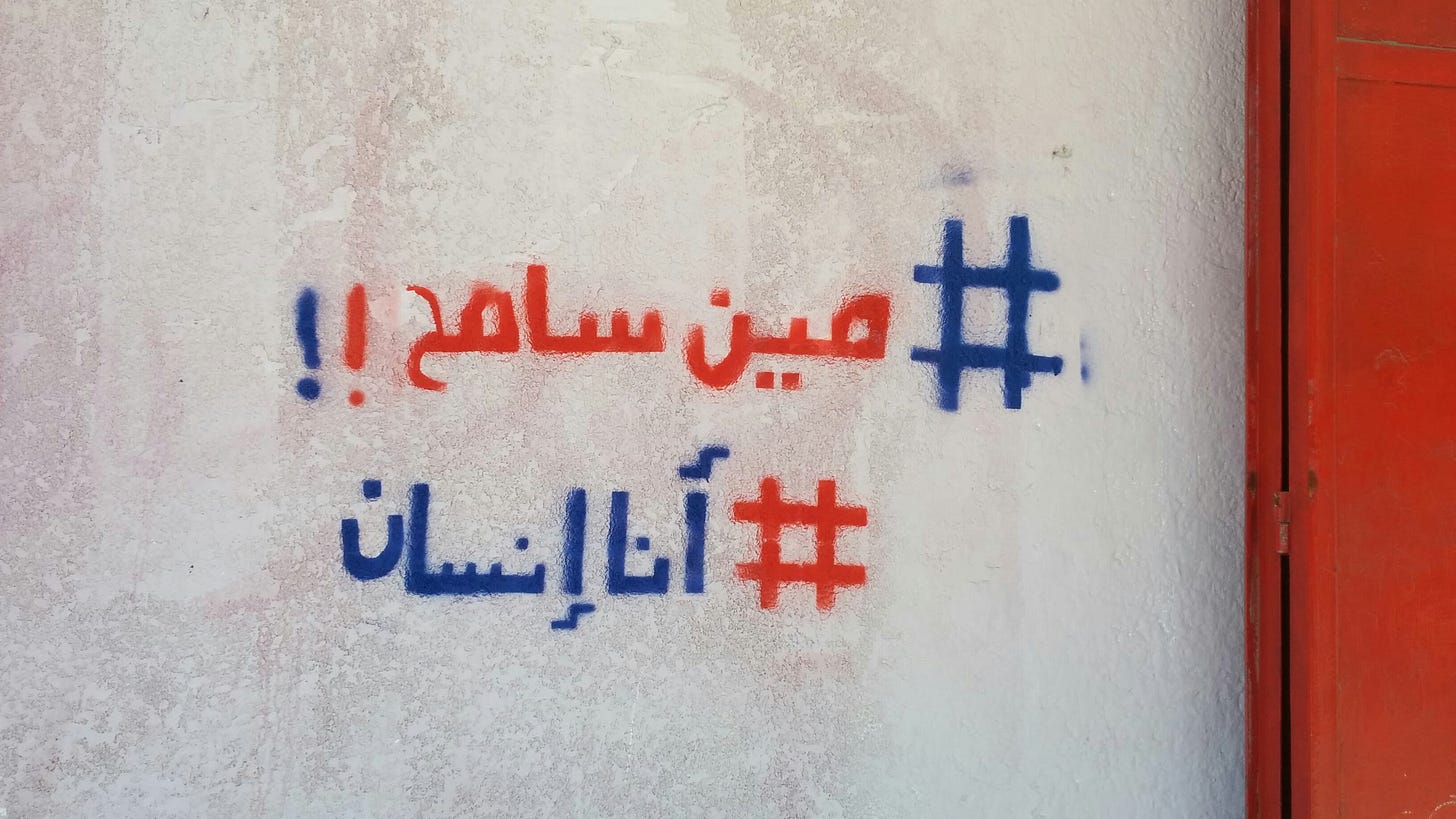

I only add this context — especially that I remember her being shy — because I was, and am still, amazed by the game they’re building. It’s called Palestine Skating Game: imagine Tony Hawk, but the protagonist is a woman in a headscarf skateboarding and rollerblading around Palestine, and the goal is to spray paint the big, ugly concrete walls that litter the landscape without getting shot by the Israeli Defense Forces, the IDF. The game is bold and funny, in a very dark way. I love it because it speaks so much, I think, to the powerlessness and frustration so many Palestinians I’ve met feel.

(They’re looking for designers, engineers, and funding, by the way. If you have any interest in learning more at all, please ask.)

So anyway, back to Dina. I was emailing with her and her confounder every few weeks right up until October 7th, when the tone of our emails unsurprisingly changed. Her cofounder outside Gaza would email me updates on the game and on Dina, and I would invariably reply asking, as tactfully as I could, if Dina was still alive.

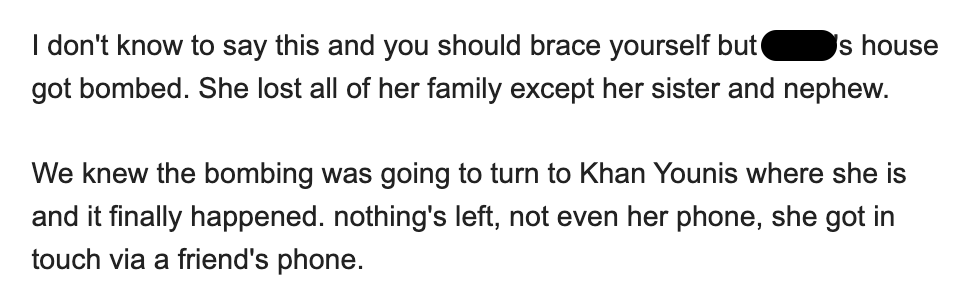

We did this every few days for a while, and finally I received this email from her cofounder on December 7th:

I’ve reread this email several times since — trying, maybe, to understand how it might feel to lose so much, so quickly. Which is of course impossible for me to understand.

A week later her cofounder again wrote to say he hadn’t heard from Dina in a few days. I replied offering to reach out to others who might have been in touch with her, and signed off the email saying “hoping for the best….” (Email is a horrific medium for communication about things like this, I’ve come to learn.)

He replied to me hours later:

“I think this might be it,” of course, is a way of saying, “I think Dina might be dead.”

We learned a few days later that she was okay, thank goodness — or at least, that she’s okay for now.

I don’t tell this story to elicit pity. I tell it to illustrate the incredible impact this is having on millions, and probably tens of millions, of people. And not just in Gaza, but around the world. Over 21,000 Gazans have been killed in this conflict thus far, and Dina isn’t even one of them! She doesn’t even show up in the statistics. But see how widely even her story reverberates.

Well, that’s a wrap I guess? If you’re new here, I promise these posts are usually more fun — lighter — everything! But it’s hard to do that with this topic, especially right now.

Thank you for reading if you made it this far. Stay tuned, and stay well.

Song of the Week: MC Abdul — The Pen & The Sword. MC Abdul is a 15 year-old rapper from Gaza who now lives in Los Angeles.