What it (Was) Like to Visit Gaza — Part Four

Crossing into Israel via Erez, and Closing Thoughts

This is the last installment of the “What it Was Like to Visit Gaza” series — thank you for joining me all this time if you’ve stuck it out.

I’ll likely do a follow-up post in following weeks but it’ll be a bonus post. Next Thursday we’ll be back to our regularly scheduled programming talking about (generally) more innocuous topics around how the internet is changing the world.

If you’re just catching up, this is the fourth installment of a series based on visits I made to Gaza, Israel and the West Bank in 2015 and 2017. Parts One, Two, and Three are here, and we released an abridged version of this via podcast if you’d rather listen than read. Though the pod definitely cuts out a lot of content, and lacks the photos I’m putting in these posts.

Finally, as I’ve mentioned, some great people from Gaza Sky Geeks have started an eSIM drive to help Gazans stay connected. You can donate an eSIM or three here — it’s an easy, relatively inexpensive way to make a big, real impact for people in a very desperate situation.

There’s been a lot of mention of the Erez border crossing linking Gaza to Israel during this war, usually in the context of food, medical supplies, and military troops coming in. But there’s little information on what it was like to go across the border before this war started, so I’d like to talk about that now.

Every time I’ve come back to this essay, I focus a great deal on what it felt like to cross the border. And I could never really put my finger on why, but I heard an interview in October with Mohammad Alsaafin, an Al Jazeera journalist who grew up in Gaza, and he described the experience at length in much the same way I recall it.

I think it’s that for me — and I suspect others too — the experience of crossing the Erez border into Israel is perhaps the best, most concise symbol I can conjure to illustrate the way in which a great number of Palestinians, and especially Gazans, experience the power of Israel in relation to their own lives.

It’s worth keeping in mind that, for almost any Gazan lucky enough to get a permit to leave, this border crossing is their first physical interaction with the outside world — and with Israel. For most, it’s probably the first time they’ll ever interact with an Israeli at all.

And most Israelis, of course, have never met a Gazan. Needless to say, such strict separation of the populations likely does little to help resolve this conflict, and probably is a great aid to anyone — on either side of the wall — wanting to incite anger against either Israelis or Palestinians.

It’s much easier to make monster of someone you can’t see.

There’s no airport in Gaza, by the way. Israeli airstrikes destroyed the radar station and control tower in December 2001, and bulldozers later cut across the runways.

And one might think that with all that water, Gazans would leave by boat, as refugees from North Africa have been doing for years. But the Israeli navy has a long history of intercepting boats to and from Gaza beyond a relatively tight perimeter, and fisherman risk being fired at if they go too far out in the water. This isn’t some crazy left-wing stuff — this is from the United Nations and published in the New York Times in 2022, which says there were more than 300 “shooting episodes” that year, and 14 fishermen injured.

The Erez border crossing sits at the northeast corner of Gaza, about 50 miles south of Tel Aviv. Close enough you could get there and back on a long Saturday bicycle ride when the weather’s nice, which it very often is.

Given the lack of an airport and freedom to leave by sea, there are only two outlets from Gaza out to the rest of the world: via Erez into Israel, and through Rafah into Egypt. I described in Week Two of this series how my friend Lina was able to escape through the Egyptian border during the 2014 war, but that is exceedingly rare. By and large, nearly anyone going into our out of Gaza leaves via Erez into Israel, which means they need a permit from Israel to do so. (Many have argued during this war that Egypt should allow in more Gazans, but I’d like to focus on the experience of the average Gazan here. For the vast majority, the Egypt crossing is not an option.)

When you leave Gaza via Erez, you pass through multiple layers of border control — several small border crossings, if you will. First you pass through the Hamas checkpoint, and then drive a few minutes further, and get out of the car at a Palestinian Authority checkpoint. And then you walk ten or fifteen minutes to the Israel checkpoint, which is much, much bigger and more formal.

Both the Hamas and Palestinian Authority checkpoints are small, and a bit ramshackle. The Hamas check consists of little more than a few men and a bag scanner, and takes about three minutes to cross. One of the times I entered Gaza one of the men pulled a tiny bottle of shampoo from my bag and smelled it, checking for alcohol. He laughed when he realized what it was, and handed it back.

After you pass through the Hamas checkpoint you get to the Palestinian Authority (PA) one, and it isn’t much either. There’s a small concrete patio under a corrugated metal roof, and rows of secured plastic seating beneath a sign advertising “Free Wi-Fi”. There are lots of seats, though I never saw more than a few people using them. And there’s a small booth with a few windows where Palestinian Authority men check your passport.

It feels very informal, like you’re paying to see a film at a drive-in theater, maybe.

After you make it through the PA checkpoint, you start on foot to the Israel border. You enter a kind of path enclosed by wire fencing — like an above-ground tunnel, or kind of cage — and you walk for fifteen minutes toward the border wall. It’s a big white wall, studded with guard towers. The actual Israel border building itself looks like a sort of dystopic, militant gray IKEA, and as you walk in this tunnel-cage you slowly approach it.

There’s a few golf carts zipping people up and down the tunnel too, offering rides for those who can’t, or don’t want, to walk.

As you walk along the path, you pass by fields — no one living there, no crops, just fields. This is the “no man’s land” separating the wall from the rest of Gaza, the area that the Israeli guard towers and ground sensors that can trigger automated machine guns are meant to keep clear. And it’s presumably why we’re walking inside the tunnel / cage thing, to the border.

There’s a road to one side of the path leading to a large gate for trucks to go through, and the last time I left Gaza some men were working on it, under the hot sun. They smiled and waved at me, and I wondered if they’d ever left Gaza themselves, if they’d ever been on the inside of the fenced path like I was.

One thing you notice as you approach the Israeli checkpoint is that you start to see cameras — more and more of them inside the tunnel, pointed at the walkway. And it’s a small walkway, so there’s not much else for the cameras to look at. It’s just you.

The tunnel-cage-path leads you directly to a heavy metal gate, set into the wall of the big, militant IKEA. There is no one there to greet you. It’s just the door, and a camera above it. I was prepared for this journey, told step-by-step what I should do at each place, and I knew at this point I was supposed to look up at the camera, and smile, and wait.

Eventually you hear a click, and the door opens. You walk into a room several stories tall (again, like an empty, concrete warehouse.) It’s filled with light from outside, and completely empty, except for a metal table in the center. Again, I was told what to do: you heave your bag onto the table and unzip the whole thing, display your t-shirts and shoes and underwear to another camera somewhere above, to show there’s no guns or bombs inside.

There’s no signal to indicate you’re done with this step. You just wait a few seconds until it seems like the camera has seen what it needs to see, and then zip your bag back up and pull it off the table. You walk across the room to a one-way metal gate with horizontal spokes, like you’re leaving the subway. And you wait.

You wait there until you hear another click, and then you walk through the gate.

You walk down a cavernous hall with concrete floor and corrugated walls and a high ceiling of iron beams. At this point, if you’re crossing the border by yourself, you haven’t interacted with another human being since leaving the PA checkpoint twenty minutes earlier.

You enter the large, central interior of the building. It feels like walking out onto the floor of a gymnasium. You can see Israeli guards in a big-windowed office maybe thirty feet above you, on the far side of the room. Some of the guards sit at desks using computers and phones, and others watch the floor, and you, below. A balcony extends from the office out into, above, the floor of the main room.

There’s a luggage belt to the left when you enter the interior space, zooming off somewhere in the building, like at the airport. And between where you stand and the far end of the room, there’s a labyrinth of chest-high glass walls framed by metal, studded with glass-and-metal gates topped with red LEDs. It feels like a TSA checkpoint from hell.

Scattered among the maze of glass and metal stand a few Palestinian guards. One waits beside the luggage belt as you as you enter the room, and places your bag on it to be whisked away.

He asks you to walk through a metal detector, and then pats you down. He speaks into his radio to the guards in the office above, and you stand together and wait in the little glass-and-metal corral you share, making small talk, listening to your breath. You try not to fidget, conscious of the eyes of the IDF guards above. The last time I went through the border, I was the only person going through — if there was anyone to watch crossing the border in the whole concrete fortress of a building, it was me.

After a time, the LED above the gate flashes from red to green, and the guard waves you on to the next corral. Some iteration of this happens several times: another guard, another metal detector, another LED turns from red to green, and another gate opens.

I still don’t know what caused it on my last trip through, but after I passed through one of the metal detectors and the guard radioed up to the office, we waited for the green LED but it never came.

The guard spoke into his radio, and we waited some more. His radio crackled a response, and he asked me to walk through the metal detector again. I did, and he radioed, and we waited. His radio crackled and the guy gave a slight groan, and asked me to walk through the metal detector a third time.

As I entered the metal detector again, an IDF guard strode out of the office onto the balcony above us, and watched me. He held a large automatic rifle. He leaned against the railing and watched as I passed through the metal detector for a fourth time, and I tried my best to look relaxed as we waited, again, for the green LED.

It finally changed color, and the Palestinian guard bade me farewell. The IDF guard went back into his office, and I breathed a sigh of relief and continued on.

The maze of corrals leads to a smaller room where there’s only a Palestinian guard and the end of the luggage belt, and you wait another thirty minutes or more for your bag. It’s clear it’s been thoroughly inspected once it comes, socks and souvenirs and underwear reshuffled and repacked in a heap. You spend another thirty minutes putting it all back together.

And then finally, you approach the Israeli passport window. If you’re me, an American visiting Gaza, that’s the end of the journey: welcome back to Israel. The last time I left Gaza, it took me hours to get to that point — I walked out into the hot white sun and hoped the car waiting to take me back to Tel Aviv hadn’t given up waiting.

So that’s my experience as an American. If you’re Palestinian, I have no idea what happens after you get your bag and approach the passport window. Nor, of course, what it’s like to be in the big room full of metal and glass, waiting for armed guards above to let you through, gate by gate.

It’s worth saying again, that for nearly every Gazan lucky enough to obtain an exit visa from Israel, this is their first experience of the country. That IDF guard with the automatic rifle looking down at me from the balcony might be the first Israeli they ever see. For Inas, the sixteen year-old runner I described last week — if her exit visa hadn’t been canceled so she could compete in the race in Bethlehem, this would have been how she got there.

I think why I want so badly to describe the border crossing is to help you understand how incredibly dehumanizing of an experience it is. The thing I keep coming back to is that I felt like an ant: alone in a big empty room, examined from above by cameras, watched by people I could not see nor talk to.

And if this isn’t clear from my description, then I’ve failed at describing it.

You walk through a caged path to bypass a no-man’s land with sensors and automated machine guns that can kill you, up to a door where you see no one, but only smile at a camera. And then the door opens — or maybe it doesn’t.

You open your bag to show to another camera, and another door opens. Or maybe it doesn’t.

And then you walk out on the floor of a big gymnasium of a room, where a man with a gun thirty feet above can watch you below. And you wait to go gate-by-gate through a maze, the doors of which are controlled by someone you cannot see.

Is there a better description of a dystopia? That may sound hyperbolic — but really, is there?

I don’t think it matters where you stand on this conflict. In that moment, you feel like an insect. You feel like a suspect.

Imagine, like Inas, you’re a 16 year-old girl walking through that border.

Would this experience make you trust the country you’re about to enter? Or fear it?

The last time I went to Gaza via Erez, I brought along my DSLR camera, hoping to take some nice photos. (Instead of, you know, the grainy old cell phone ones I’ve been including in these posts.)

I casually mentioned the camera to the nonprofit employee escorting me across the border, and he gave a look of shock. He grabbed his phone and called for another taxi to meet us and take the camera, saying I’d have to retrieve it at the organization’s Jerusalem office the following week, when I left Gaza.

“It’s something about the removable lens,” he apologized. “The border guards don’t want them coming into Gaza, except with journalists. They count the lenses going in and out.”

I said I was sorry — I’d had no idea. Somehow I’d never heard this on my first visit.

“It’s news to me too,” he said. “I honestly never know what to expect, the border rules change so often.”

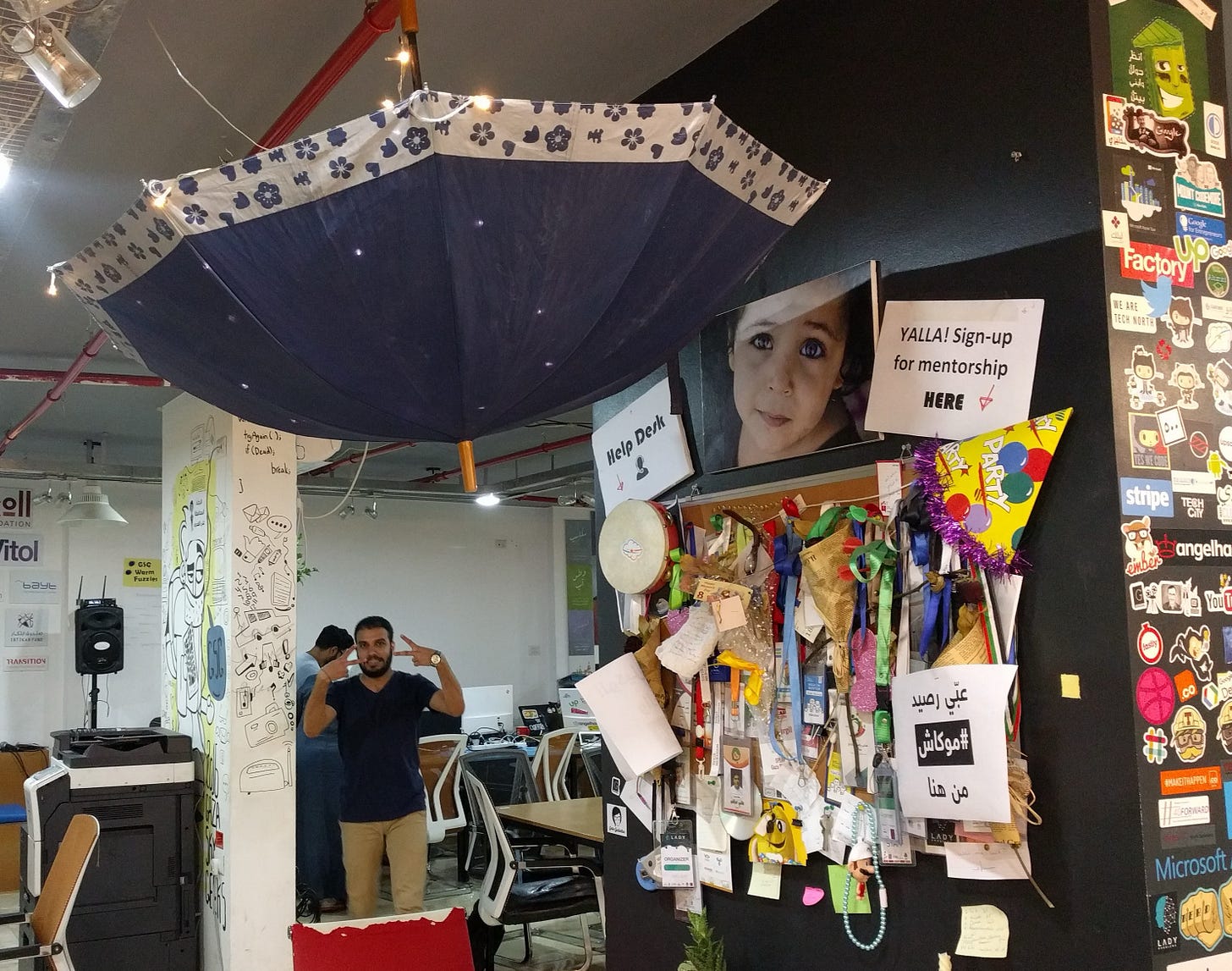

Indeed, the border rule changes are such a problem, I met a team at the tech accelerator that week making an app to help with it. A whole app, just to help people make it through the Erez border crossing. The idea was to crowdsource information from aid workers and journalists as they crossed to help others better plan their journeys. The app would inform users of wait times, items banned and allowed through the border each week, and more.

We made it through the border without a hitch after that, and met Reema, an American working with the tech accelerator, on the other side, in Gaza. She breathed a sigh of relief when she heard the camera story, and said another volunteer had crossed into Gaza that morning without trouble, too. Two easy crossings in a day, I learned, was an anomaly.

“We’ve used up all our kismet for the week,” said Reema. “No more kismet! Nothing bad can happen this week, we have none left.”

I love the word kismet — the word comes from Turkish, and Arabic before that, and it means something like “fate,” or “luck,” or “karma.” I encounter the word often in the Middle East — and especially in Gaza.

To refer often to kismet, I think, isn’t all that different from relying on fate. And to rely on fate, of course, is to relinquish some amount of agency over your own life. It is to accept the contingency of your future on the whims of some external force, to accept a great deal of it lies beyond your reach.

Kismet dictates so much in Palestine, whether you’re a startup entrepreneur, Olympic marathon hopeful, or Fulbright Scholar.

Will the exit permit come through? Will the border stay open? Will the internship have funding when it does?

When will the next war comes, and what will it take?

A few days after kismet got us into Gaza without trouble, I mentioned to a friend there, Eli, how nervous I was waiting for news on a job offer. This was early in my time at Google, when I’d reached the end of my contract and had applied to become full-time. I had interviewed the day before my flight to Gaza, and I knew if I passed the interview, I would go home to a full-time job. And that if I didn’t, I’d have to scramble to find something new.

Eli laughed when I told him this. “You’re in Gaza now — so many worse things can happen to you! A job is nothing.”

I received the job offer that night, and shared the news with Eli the next morning. He congratulated me, said we should go out for juice.

Time flew by the next few days, and we never got juice. I assumed he’d forgotten, which was of course okay. (We were in Gaza; a job means nothing.)

But as I scrambled to leave the tech office for the border, Eli and several others opened the door, carrying in a large cake. They shouted congratulations, laughed, recorded my shocked delight with their phones.

And there was a firework perched atop the cake, spitting sparks into the office. I looked around the room at the papers, the laptops, the smartphones piled around. And I felt nervous.

But I was the only one. Everyone else just smiled and ate the cake.

Every time I’ve left Palestine to go back to Israel — twice from Gaza, once from Ramallah — I’ve experienced a kind of culture shock. I struggle to describe it, but it feels to me something like going from a war zone into the heart of New York City.

Every time I get to Israel I’m struck — struck — by the seeming normalcy of it all. I’m in Gaza in the morning taking a saltwater shower, driving past the rubble of a war that ended three years before, watching a woman drive a wooden cart pulled by a donkey. And then I pass through the border, with its guard towers and razor wire, guns and dogs, and onto Tel Aviv, where there’s beers on the beach and motorized scooters and fashionable, gorgeous people waiting in line to get into nightclubs. It’s, well, bonkers.

One thing that’s really struck me in the coverage since the October 7th Hamas attack is how surprised so much of the world seemed to be by it. And to be clear: I don’t want to diminish how awful that attack really was. It was awful.

But the surprise of it is what, well, surprised me — and I think it’s tied to that experience I’ve had of feeling like I’m in a war zone in Gaza, and something similar in the West Bank, to something like New York City when I go to Tel Aviv. I think it’s that the status quo in the two places feels as different as they can be: one has felt like to me it’s in a state of relative peace, and the other in a state of perpetual war.

I’d like to share two quotations I’ve come across from coverage of this conflict, from both the Israeli and Palestinian sides.

The first is from Tom Friedman in the New York Times:

“I asked Liat Admati, 35, a survivor of the Hamas attack… what would make it possible for her to go back to her Gaza border home, where she was raised. ‘The main thing for me to go back is to feel safe,’ she said. ‘Before this situation, I felt I have trust in the army. Now I feel the trust is broken. I don’t want to feel that we are covering ourselves in walls and shelters all the time while behind this fence there are people who can one day do this again. I really don’t know at this point what the solution is.’”

Now contrast that with this passage from NPR, describing the lack of an airport in Gaza. The story profiles a teenage boy named Ibrahim Adwan living there.

“The 14-year-old spends his out-of-school hours making a few dollars by collecting metal at the ruined airport, and taking it by donkey and cart to sell at the scrap market. At present, there are fresh pickings, as the airport was shelled in the recent war. He has never seen an airplane fly out of Gaza, and does not believe he will anytime soon. ‘People abroad have a life, but here it is meaningless,’ he says. ‘After one or two months, there will just be a war again.’"

That quotation, by the way, is from 2014 — ten years ago. If Ibrahim is still alive, he’s now in his mid-20’s. And he was right, wasn’t he?

Contrast these words again with something my friend Lina told me in San Francisco, during that same lunch in 2020 when she told me stories about the war — she’s the startup founder and hardware engineer who escaped Gaza in 2014. She told me how her parents had recently moved to the beach, where Israeli missile attacks are apparently most frequent. For obvious reasons, this concerned her.

But her parents just laughed, and said “At least we’ll die with a view!”

I guess this is the biggest thing I wanted to talk about here — is that even if this war ends tomorrow, if things were to magically go back to the status quo of October 6th, it would still be terrible for most Palestinians. I imagine most would of course prefer that to the current situation, but it would still be terrible.

The woman in that Thomas Friedman piece talks about how she felt “safe” before this. But I would be curious to learn how many Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza have ever felt “safe” in their daily lives.

I think that’s big — that goes way beyond this current war. When I hear Palestinians talk it’s often about safety, and freedom. “Freedom of movement,” specifically, is something you often hear around the Palestinian cause — it’s a freedom most of us in the rest of the world take for granted; it’s not even something most of us would consider a “freedom.”

So I guess this is about where I wrap up. For those of you still reading, thank you — I hope you’ve found it worthwhile. If there’s any lasting impression I can wring out of this, I hope it’s the realization that Palestinians are people too — they want the same sense of peace and freedom that we all do. It seems silly to have to say that, but I think we do.

My real hope in this is that whenever this tragic conflict ends, whatever happens, we won’t return to the status quo. I don’t know what things should look like after this to ensure peace and freedom for Palestinians and Israelis alike, but October 6th, the day before the Hamas attack, isn’t it.

And finally, especially if you’re American, know your voice matters, immensely. Our country helped create this conflict — and it is in our power, even our responsibility, to help end it.

My fear is that whenever this current war winds down, international attention will move away. American media will turn its cameras and microphones to the US election, and our social media feeds will go back to whatever it is that influencers were doing before they started weighing in on geopolitics.

Most of us will return to the way things were — but Palestinians, especially, won’t be able to. And even if they could, “the ways things were” were never good enough. I hope if nothing else comes of all the awfulness that’s taken place in Israel and Palestine since October 7th, it’s an international recognition of the need that things need to change — and the American, especially, recognition that we have the power to make that happen.

Thank you.

Song of the Week: Pharrell Williams — Freedom. I somehow just came across this song, and I can’t think of a more fitting one for this post. The video is beautiful too.