The Time the US Built a Fake Cuban Twitter

Weaponizing social media to influence politics isn't as new, or surprising, as it may seem.

I first published this in The Hill, and thought readers here might enjoy it too. Note this was written and published about a month ago, the day before the legislative TikTok ban deadline April 5th.

Most people likely missed the news of the deadline completely — at most other times it would have been a prominent story, but arriving as it did days after Trump announced his “Liberation Day,” tariffed a bunch of penguins, and tanked the global stock and bond markets, it was doomed to absolute media obliteration.

Anyway, here it is — enjoy.

As tomorrow’s TikTok ban deadline approaches, let us reconsider one of the more compelling arguments for its forced sale: the threat that the Chinese government may use the app to influence U.S. politics.

Various influential voices, including the ACLU and Electronic Frontier Foundation, argue this does not present sufficient rationale to override free speech concerns — that the ban must require, in the ACLU’s words, “real evidence of serious harm.” But we must ask: Is it even possible to detect real evidence that TikTok is causing harm to our politics before it’s too late to stop it?

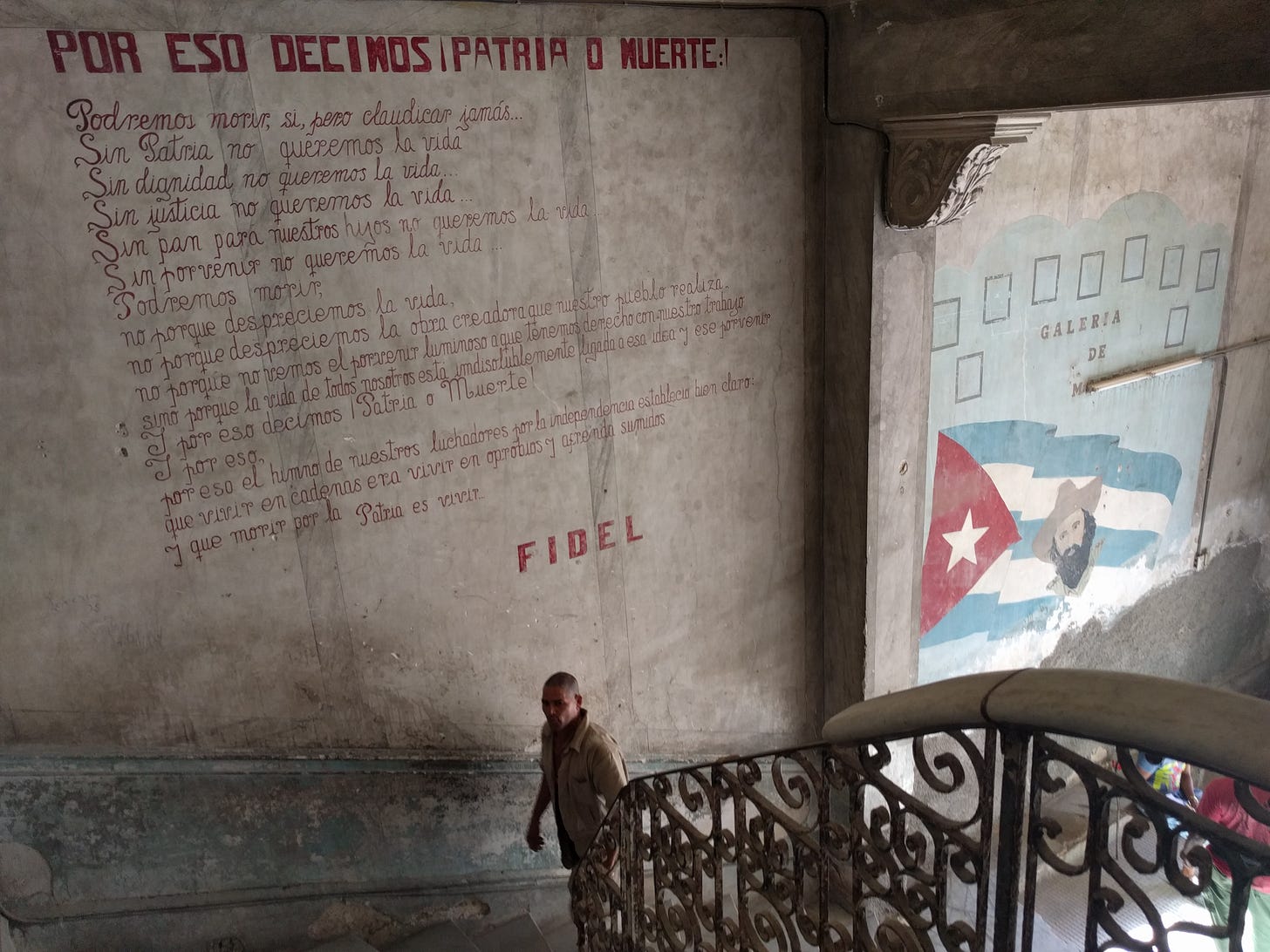

History provides a useful parallel. In 2014, it was revealed that the U.S. Agency for International Development had covertly designed and launched a Twitter-like app called ZunZuneo in Cuba.

The Guardian reports that U.S. government documents described plans to build a user base through “non-controversial content” such as “news messages on soccer, music and hurricane updates.” Only later would they “introduce political content aimed at inspiring Cubans to organize ‘smart mobs’” that might trigger a “Cuban spring” and “renegotiate the balance of power between the state and society.”

One memo explicitly stated: “There will be absolutely no mention of United States government involvement.”

These words are eerily relevant today. What the U.S. once planned, we must consider China capable of doing through TikTok.

And we have, of course, already seen the platform turned toward political ends within the U.S. When first facing legislative threats, TikTok launched a notification urging users to call their representatives — but tellingly, targeted only to those with House members on the Energy and Commerce Committee.

Earlier this year, TikTok pushed a message to all U.S. users thanking President Trump for “providing the necessary clarity and assurance,” allowing its continued operation. And just this month, the app notified some American users with a message encouraging calls to senators to “vote no on the TikTok ban.”

Free speech concerns raised by critics of the proposed bill should not be dismissed lightly. But we must balance them against considerations that have guided media regulation for generations in this country. Nearly 100 years ago, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1927, which required licenses for broadcasters and for “broadcasting to serve the public good.” And since 1934, the Federal Communications Commission has barred exclusive foreign ownership of U.S. media entities.

Critics note these regulations emerged for “a limited set of broadcast frequencies,” constraints that don’t apply to the internet. Yet as Americans continue to shift from traditional to digital media consumption, we’re increasingly left without a regulatory agency to ensure the media serves to benefit society at large.

Existing regulation was never designed for an era where foreign entities can directly reach one in three American adults through the unique isolation of a social media feed. And just as our media technologies change, so must our regulatory approaches.

Some argue that forcing TikTok’s sale doesn’t go far enough — that we need broader legislation preventing any individual or small group from holding outsized influence over our politics and social media. And I agree. But addressing these concerns becomes far more feasible when those individuals are American citizens, and subject to American laws.

As Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson point out in the recent book, “Abundance,” American progressives too often strive for “the perfect” at the expense of “the good.” A forced TikTok sale should be viewed not as a complete solution, but as a crucial first step toward advancing other rules ensuring social media doesn’t further erode American society.

Recent bipartisan legislation seeking to repeal Section 230 is a particularly poor example of this, and would lead to disaster if passed. But one piece of misguided legislation shouldn’t scare us away from pursuing its other, better forms.

The internet presents unprecedented challenges to our nation’s education, mental health and democracy itself. While we must proceed carefully, it is increasingly irresponsible to survey the landscape of American media and declare that nothing can be done to fix it.

Without this, we face the risk that platforms like TikTok could, just as ZunZuneo intended, begin subtly weighting “non-controversial content” toward that which might “renegotiate the balance of power” — all while we wait for “real evidence of serious harm” that might come too late.

Now more than ever, we must reconsider what it means for our media to serve the public good in the digital age, and to imagine a responsible regulatory future that ensures it does. The forced sale of TikTok should be seen not as the end of this conversation, but as its necessary beginning.

Song of the Week: Buena Vista Social Club — Chan Chan

Find all past songs of the week & follow the playlist for updates here 🎵🎵

I generally agree with your take here. I'm wondering if it could not be bolstered with any evidence of Russia's interference in US society and politics through Social Media. Like you said, this is hard to prove, but at least during Trump 1 they had an actual agency that was dedicated to this task. Though, perhaps that's a counter argument to banning TikTok: foreign agents don't need to control the whole platform to be able to manipulate the narrative. For example, TheSoul Publishing doesn't need to own YouTube to be a massive content farm that occasionally spews pro-Russian propaganda (my personal conspiracy theory tin foil hat take is that they also create purely idiotic content just to dumb down the general population so that the propaganda lands better when it comes out. But maybe blaming Russia for our gullibility is just too far).