The TikTok "Ban" isn't as Strange as it Seems

Tech protectionism isn’t new — and maybe not always bad

Last week, the US House of Representatives passed a “TikTok Ban.” Or H.R.7521 more precisely, the “Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act.” It passed by a surprisingly wide bipartisan margin of 352 to 65.

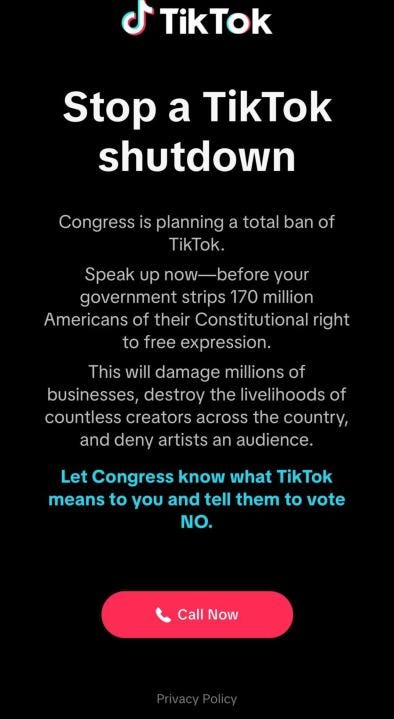

In truth, calling the proposed legislation a “ban” is inaccurate, and I’d argue irresponsible. But regardless it’s caused no small amount of controversy, with some saying the bill should think bigger, TikTok’s CEO urging users to “protect their constitutional rights,” and the app itself sending in-app messages to teens — but not always their parents! — urging them to call Congress.

(This is a topic for another day, but regardless of one’s beliefs around this particular issue, the idea of companies leveraging their software to encourage users to take particular political action — as did Uber and Lyft in 2020, urging Californians to vote for Prop 22, to the benefit of these same companies — should probably make us all feel uneasy. I’m all for apps encouraging users to vote, but not to “Vote for X.”)

The bill also sits at the intersection of numerous topic areas worth discussing:

The Chinese government’s blurry relationship with “private” tech ownership,

The wild incongruity in the US between policies regulating traditional broadcasters while mostly ignoring modern social media, and

The role of protectionism in dictating foreign media operations — something rare in recent US history, but much more common elsewhere around the world.

To start, the proposed bill isn’t a “ban,” but will likely only require TikTok sever any perceived ties with the Chinese government — which would probably lead to a (very $$$) sale to US owners. As Scott Galloway notes, “A ban is a terrible use of words… there’s too much money.” Even if the bill becomes law, he argues, there will be a mind-boggling amount of Silicon Valley cash thrust at ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, to overtake app ownership. And he’s probably right — though if TikTok is indeed a powerful tool for propaganda and misinformation, we should probably beware whatever billionaire investors are salivating to purchase it here, too.

It’s challenging to voice strong opinions on this without looking like a megaphone-gripping fear monger raving about the CCP’s imminent takeover of American minds. But much as the company’s owners might say otherwise, the Chinese government has a long history of deeply meddling in the workings of tech companies with ties to China, as ByteDance does. The entire controversy, in fact, over repeated historic attempts by Google and others like it to enter China has focused on the government’s insistence on corporate control. Control that can, among other things, involve censorship demands, as well as requests for data on perceived dissidents.

Regardless of the particular relationship between China, TikTok, and the US, there’s precedent for this bill that moves beyond fears of any one foreign power. The FCC has had a rule in place since the Communications Act of 1934 — for nearly 100 years — limiting foreign ownership of radio and television broadcasting to a 25% share. Though the rule was recently somewhat relaxed, in 1985 it led Rupert Murdoch to relinquish his Australian citizenship and become a US citizen. Which then allowed him to expand his media empire into the right-wing propaganda machine it is today.

We don’t tend to think of social media companies as “media” on par with broadcast television and radio, but we should — and in fact, one Supreme Court case in the news now revolves around just this question. TikTok is increasingly viewed as a source of news, especially by Gen Z. And as social media expands to consume a growing share of consumption relative to traditional broadcast networks, it is increasingly important to create novel guardrails around it. For nearly a century the FCC created rules for traditional broadcasters aimed at benefiting the public good, and it can do the same for social media now.

Protectionist Vibes

I think what may be most shocking about this bill for many, though, is that we aren’t accustomed to the US government “banning” much of anything. At least for the last few decades, there’s been the appearance of an uninhibited global market dominating our economy. But as we’ll see, government controls over the ownership and operation of tech companies are relatively common elsewhere.

The term “protectionism” usually refers to economic tariffs on foreign products — and sometimes even complete bans — aimed at protecting a country’s domestic industry. So the term in this sense doesn’t quite pertain to the case of the TikTok bill today, the aim of which centers primarily around national security. But the mechanisms and effects look quite similar.

Given the internet’s unprecedented fluidity across national borders, new concepts with protectionist flavors have sprung up over the past several years, such as data localization. Indian lawmakers, for instance, proposed — and later scrapped — a policy requiring any company with digital data on Indian citizens to maintain it on servers in the country of India itself. (If it’s hard to imagine this because terms like data and “the cloud” evoke ephemeral notions lacking physical counterparts, my two posts discussing the internet’s physicality may help.) This policy would have deeply impacted companies like Google, Meta, Amazon, and Netflix, and smaller ones too.

While the motivations behind India’s data localization don’t exactly resemble the typical protectionist goals of shielding domestic industry from foreign competition, they don’t not resemble them, either. According to the Atlantic Council, Indian policymakers were interested in pursuing data localization for many reasons, “including to impose costs on foreign companies, boost India’s data storage industry, increase Indian government oversight over the storage of data related to Indian citizens, and…. enable better Indian law enforcement access to crime-relevant data held by US companies.”

And India’s no stranger to banning tech products outright. In 2016, the government blocked Facebook’s Free Basics and other “zero-rating” offerings allowing for no-cost data access to a limited set of apps. (This came after a long, contentious fight in which Facebook — like TikTok today, and Uber and Lyft in California in 2020 — appealed to users to influence public policy.) And though I first learned about TikTok while in India years ago, in 2020 the government banned it and over 60 other Chinese apps.

Especially pertinent to the TikTok debate in the US today, China has historically blocked many foreign companies from operating within its boundaries, and heavily restricts ownership of internet service providers (ISPs) too. Granted, much of China’s restrictions on foreign internet operations are aimed at controlling what its citizens see — akin to internet censorship in Russia, Cuba, Turkey, Thailand, and many other countries around the world.

To that end, China, Russia and others have begun advocating for “cyber sovereignty,” another policy with protectionist flavors. While commonly framed as an anti-colonial movement pushing against Western hegemonic powers — at first blush, it’s easy to wonder, why shouldn’t countries have sovereign control over citizens’ cyberspace?! — in reality it would greatly enable repressive governments, allowing for much greater control over the online words and actions of anyone challenging them.

But for today, let’s focus on the “protectionist” aspect of foreign tech restrictions — restrictions aimed, at least in principle, at benefiting the citizens under their purview.

Even the European Union has shown greater willingness to enact policies protecting its citizens than the US and most other large, democratic governments. The past five or so years has seen a raft of legislation and large corporate fines aimed at protecting European citizens online. And because it’s frequently easier for large companies to make a single change rather than design a set of country-by-country piecemeal policies, these benefits can “trickle down” to users elsewhere.

You Give Protection a Bad Name 🎶🎶

While we’re talking about technology protectionism, let’s spend a little time looking at the goods and bads of protectionist policies overall. And I can hear you yawning! But I’ll try to make this as spicy as I can 🔥, because I believe it’s important.

Since at least the time of Reagan and Thatcher when a wave of neoliberal, laissez faire, free-trade thinking gained an increasingly tight hold over Western governments, protectionism has garnered a bad name in economic circles. Often this is for good reason, as in highly-developed economies like that of the United States where supply chains form a complex web of global dependencies. Protectionist policies in this case can even harm the constituents they’re meant to protect, as when in 2018 American auto manufacturers opposed President Trump’s 25% tariff on imported auto parts. The tariff would raise their costs, they argued, which would then hurt American consumers — who, researchers predicted, would face a cost increase for popular car models from $1,400 to $7,000. (Even this weekend, Trump claimed he’ll implement a “100% tariff” on certain imported vehicles if elected again. I imagine we’ll soon hear about the predicted impacts of that on American prices.)

But these same free trade, financial liberalization policies have been pushed on developing economies by economic aid institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank for decades, too. Protectionism, so the story goes, is bad, full-stop — no matter if the country doing it is big or small, rich or poor.

Some disagree though, and equate this to Western, wealthy nations “kicking away the ladder” of development. The modern taboo against protectionism, they argue, has hindered the growth of emerging economies in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia, forcing them to compete on the global stage before they’re ready.

Indeed, America, Europe and other wealthy regions today maintained heavily protectionist policies for decades — even centuries — of early growth. And like baby animals gaining strength and wisdom at home before going out to face the big, scary world of predators, this early protectionism allowed these nations’ economies to grow big and strong before competing on the global marketplace.

But there’s a lot to dig into there, so we’ll save it for another post. Stay tuned!

Song of the Week: Cui Jian — Nothing to My Name. The song became an unofficial anthem of student protestors and activists during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. Within a few years, Jian was banned by the government from playing major Chinese venues for almost a decade.