And this, I think, presents an important lesson. Repeatedly, Silicon Valley brought hubris and capital to high-profile attempts at disrupting sclerotic industries — whether education or healthcare, public transportation or the delivery of the internet itself. And time and again, after a few years trying, the companies simply gave up.

These companies gave up because they realized why these industries appeared sclerotic. It’s because, unlike the ephemeral, go-anywhere world of software and “the cloud”, they saw the real world as it really is: messy, and complicated, and slow.

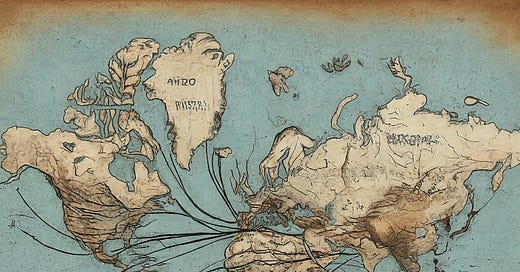

In the latter 2010’s, large internet companies set about spending hundreds of millions of dollars exploring sexy new “moonshot” strategies to expand internet access across the Global South. (Or as we call these places in industry, the “emerging markets,” filled with the “next billion users.”)

A few major companies led the push on this: Facebook and Google at first, and now satellites from Musk’s Starlink and Bezos’ Amazon. And each of these projects — with the exception of the satellites, which we’ll discuss — was eventually shut down, one by one, by their corporate owners. Often before they even saw the light of day.

I’ve wanted to write about this for a long time, and am excited to finally have the chance. I was very involved in many of these efforts at Google, and kept a keen eye on the progress of similar projects across the industry. For at least half a decade, my entire raison d’etre within the company was researching ways to improve projects aimed at expanding internet access in places like India, Indonesia, Philippines, Nigeria, Brazil, and more.

And I was committed to this. I’m often skeptical of the utility of tech products and gadgets in our lives and for the world at large, but I’ve always liked the idea of expanding internet access. Because it’s infrastructure — it’s the underlying substrate making all this other tech stuff possible, the communication and information and education and all else that made the internet such a hopeful place for so long. It didn’t matter what about the internet anyone found exciting — without internet access, none of it could even exist.

For years I was entranced by the myriad possibilities of global connectivity, an entire “village” in one place, online. And I couldn’t think of a better way to focus those efforts than through some of these projects.

But like so many others, I’m much more skeptical of the internet’s promised value today. Exploring this skepticism is, in fact, the entire raison d’etre of this newsletter. I’m more skeptical, for one, that having “one global village” online is a good thing, or even possible. And I’m skeptical of the cute idea so many of us held, ten or twenty years ago, that the internet would one day lead us all to a utopia of unified truth and understanding. (Yowza, were we in for a surprise there!)

But for a while, I was committed. I even spent a couple years trying to create an internal conference at Google bringing together everyone working on internet access projects. It sadly never happened, but I planned to call it “CONNECTI-CON,” and I was (and still am) damn proud of it.

First the Projects Sprouted Wings

So what were these efforts, anyway? Some, like Google’s Project Loon — a network of internet-connected hot air balloons — were well known outside Silicon Valley. But there were others. So many others.

Facebook and Google were the main companies pouring money and effort into this space. To this day I don’t know exactly why all this happened, but it’s easy enough to guess. The projects generated tremendous (if expensive) PR, positioning the companies as benefactors building the unified global internet village of the future. And of course, they were also a long-run investment: more Facebook and Google users, one day, might translate into greater Facebook and Google revenue.

And at least for a while there, this was surely a land grab of sorts, a brand-identity effort. Just as other companies (and tech companies too) seek to hook kids on a brand from a young age and retain them for life, Facebook had good reason to lead new internet users to believe, as a 2015 survey found 65% of Nigerian respondents did, that “Facebook is the internet.”

And Google, for obvious reasons, didn’t like this much at all.

Facebook

In 2013 the company launched the website Internet.org and announced partnerships with multiple telecommunications and phone companies. This was accompanied by a white paper published by Mark Zuckerberg asking “Is Connectivity a Human Right?”

The project aimed to expand the goal of Facebook Zero, the company’s early text-only “zero-rating” product — a version of Facebook that didn’t cost users any data. Facebook Lite, which used less data than ordinary Facebook (but not zero), was later launched in select markets. And these projects were effectively subsumed under the header of Free Basics, a suite of data-free apps available in select markets. The company created Express Wi-Fi around the same time, a series of wifi hotspot partnerships in numerous developing countries.

In 2015, the company began testing Aquila, a series of solar-powered drones that would deliver internet to the ground from over 60,000 feet in the air. And they acquired Endaga, the PhD project-turned-startup by classmates of mine at the University of Washington. A “cellular network in a box,” the company originally strove to provide local cellular access in rural Southeast Asia.

In 2018 Facebook claimed to have connected over 100 million people to the internet via its various internet.org-related projects. Though many (including myself) view that number with heaping handfuls of salt. It’s incredibly hard to measure something like this, for one. And for another, “getting connected to the internet” isn’t a one-time process, like “turning 18” or “learning to ride a bike.” And were those 100 million people connected to the internet, really, or just Facebook?

Google

When Facebook went all-in on “connecting the unconnected,” Google wasn’t about to let them hold their place in the sun alone. The company launched its own slew of internet access projects — and I’m biased because I worked on many, but I do feel better about the ethics and goals of Google’s internet effort vis-à-vis Facebook’s. Sure, Google hoped to eventually make ad revenue from the “next billion” people coming online in places like India, Indonesia, Philippines, and much of Africa. But at least they’d have access to the whole internet.

Most famously, Google began work on Project Loon in 2013, hoping to build a network of high-flying hot air balloons beaming down rural internet access. That same year, they started Project Link, partnering with internet providers in Africa to build fiber and public wifi networks on the continent. And they got into the drone game too, acquiring Titan Aerospace in 2014.

Then came many of the projects I worked on when I joined in 2015. Google Station created free wifi hotspots at public train stations around India, and then expanded to build similar hotspots in other countries. And Accelerator, which never grew big enough to gain much press, aimed to speed up public wifi in malls and other public places by storing heavy video content on local networks. (If this sounds confusing, I wrote a primer on the idea back in December.) And though I’ve left since, Project Taara is apparently still up and running, partnering with telecommunications companies to build long-distance internet fiber connections using ~light beams~.

I worked on a series of other “internet access-related” apps like Datally, which helped users better manage, and ideally save, mobile data — and thus save money. But these weren’t massively complex infrastructure projects like the rest.

Satellites & Subsea Cables

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the most recent, and most successful, iteration of sexy internet access technology: satellite internet delivered by Elon Musk’s Starlink, Jeff Bezos’ Project Kuiper, and others. Companies struggled to develop satellite-delivered internet for much of the 2000’s and 2010’s. But as technology improved and the cost of putting satellites in the air decreased, so increased the viability of companies like Bezos’ and Musk’s.

And while it’s not exactly sexy or new, both Google and Facebook continue to ambitiously invest in the creation of subsea cables linking continents to speed up internet data transfers around the globe. The companies regularly announce large investments in these cables with jaunty names like 2Africa and Pearls, Equiano, Honomuana and Tabua, Nuvem, Humboldt, Unity, Curie, Faster, Junior, Monet, Tannat, Havfrue, Indigo — and more and more and more.

But are these technologies really new, or sexy? We’ve had satellite TV for decades, after all: the first satellite television broadcast launched in 1978, nearly half a century ago. And PBS, the non-profit public broadcast network of the US — the apparent juggernaut of technological disruption! — was the one to broadcast it.

The first subsea communication cable, meanwhile, was built way back in 1850 to carry telegraph signals across the English Channel.

And Then They Fell

One by one, just as they were learning to fly — and often before — the vast majority of these big, ambitious moonshot projects shut down. This happened to no fewer than four products I worked on at Google (talk about the magic touch!), and with each, our teams were dispersed to work on other, often less-exciting, projects in the company.

Google shut down the Titan drones in early 2017, and Accelerator, the local video cache product I worked on, soon after. Facebook ended its own drone ambitions in 2018, and Free Basics — while not ending entirely — faded into the background around the same time.

The year 2020 changed a whole lot in the world, and the era of ~sexy internet~ was no exception. Early that year it was announced that Google Station, the high-profile public wifi project that ramped up five years before, was ending. The company grounded its Loon balloons the following January, and Facebook ended the Express Wifi hotspot program the year after that.

As I mentioned up top, Google’s Project Taara does seem to be moving along. I don’t know the project’s current status, but it seems they’re building technology to enable local partners, rather than coming in, guns blazing, to disrupt a whole industry themselves. And this seems smart. Google and other tech companies are good at building technology, but not necessarily anything else required to run an internet business. Local partners with experience working with local governments, obtaining permits, and building partnerships are good at the other, messy, physical-world stuff.

Struggles in the Physical World

How did these projects — some of which cost tens of millions of dollars to even begin — come to such unceremonious ends? It’s worth highlighting a few factors to see the vast gulf between how the tech industry works, and how infrastructure gets built.

For one, these projects were expensive. In contrast with the exponential “hockey stick growth” typically expected of tech products, the business model of traditional infrastructure depends on a reservoir of patience. Large telecommunications companies spend years investing heaps of money building networks — and then sit back to recoup the costs, and eventually reap profits, for decades after.

And progress was slow. Internet projects require government approvals and permits — often for each country in which they operate. And not only from FCC-like tech regulators, but also FAA-type approvers for internet delivered via balloon or drone.

For good reason too, existing telecommunications companies in places where these projects launched often viewed the new Silicon Valley entrants — notorious for disruption and innovation, flush with ambition and capital — with caution.

And while a goal of these projects was almost surely somewhat driven by desires for good PR, even this could backfire. Facebook received significant public pushback for their Free Basics program, and some critics labeled it “digital colonialism.” Many around the world criticized Facebook’s creation of a “walled-garden” in developing regions, in which users were shoehorned into using exclusively zero-cost Facebook products instead of the broader, freer (and more expensive) internet. Journalists filed stories from places like Myanmar where many seemed not to understand the difference between “Facebook” and “the internet.” And India’s government blocked Free Basics entirely in 2016, following a high-profile political battle with the company.

Sometimes Progress is Slow and Unsexy

More than all these reasons though, internet cost in the developing countries where Facebook and Google focused simply… came down. And it dropped just like the cost to access the internet plummeted in so many other places — without the need to employ drones or balloons or other “moonshot” technologies.

While the internet isn’t yet affordable or available everywhere, the price has certainly come down across much of the developing world. Reliance Jio in India serves as a remarkable example of this. The company emerged as an entirely new mobile data provider in late 2016, and offered six months of free 4G data for anyone who signed up. This was truly revolutionary for India, where data had been very expensive, and much slower than 4G speeds, for the internet’s entire history there.

Within a year, internet prices in the country plummeted to levels affordable for many even at the lowest end of the economic ladder. And the shock to the country’s internet industry caused roughly half of India’s telcos to close their doors, or merge.

What revolutionary internet technology did Jio deploy to bring affordable internet to hundreds of millions of Indian citizens in an incredibly short time?

None.

Critics point out that Jio almost surely created corrupt deals to gain preferential treatment from Modi’s national government. But as far as the technology that ultimately succeeded in “connecting the unconnected” of India goes, Jio used the same unsexy, tried-and-tested mobile data towers and underground cables delivering internet almost everywhere else.

And this, I think, presents an important lesson. Repeatedly, Silicon Valley brought hubris and capital to high-profile attempts at disrupting sclerotic industries — whether education or healthcare, public transportation or the delivery of the internet itself. And time and again, after a few years trying, the companies simply gave up.

These companies gave up because they realized why these industries appeared sclerotic. It’s because, unlike the ephemeral, go-anywhere world of software and “the cloud”, they saw the real world as it really is: messy, and complicated, and slow.

Max Weber famously said that “Politics is a strong and slow boring of hard boards.” And it seems this applies to the creation of technological projects touching the physical, social, and political as well.

They’re slow, and boring. And anything but sexy.

Song of the Week: Şatellites - Seni Sen Olduğun İçin Sevdim

"Jio used the same unsexy, tried-and-tested..." ...strategy of bribery that everyone else has used to make progress in government. I kid, I kid.

Great article, had no idea laying of underwater cables was still so frequent.

I know you're focusing on the developing world but I can't help but think about the history in the developed world and the forgotten areas of today's developed world. Internet access is a thing there too!

The internet needs more writing and thinking like this. Thank you!