Hello Tariffs... and Robots?

Some hope tariffs will bring manufacturing jobs back to America. But what if robots get the jobs instead?

Even as some say that years of global economic hardship and tariffs will be worthwhile if it means bringing manufacturing jobs back to America, the question we must ask is not *who* will staff the factories, but *what* 🤖

I’ve been wanting to write about globalization and automation for a while, and ~for some reason~ this felt like a good week to finally do it. Just a whim, I guess! 🤷

For those who haven’t seen the light of day since last Wednesday (lucky you), Donald Trump’s announcement of across-the-board tariffs on nearly every landmass on earth last week has thrown the markets, economy and my every last person / penguin’s mental health into disarray.

There are more reasons to dislike these tariffs than Donald Trump has love for his sons, but one premise particularly worth discussing — and which, to my ears, hasn’t come up as much as is deserved this the past week — is the idea that tariffs will “bring good manufacturing jobs back to America.” Let’s ignore for a minute rising consumer prices, rising manufacturing prices, and just how badly this threatens to kibosh the summer I’m hoping to spend in Europe, if they’ll even let me in.

Let’s table all those concerns, and merely ask this: if tariffs do succeed in bringing manufacturing back to America, can this lead to a bounty of high-paying jobs and, say, rejuvenate the Rust Belt? First we’ll see what globalization has done for some of the poorest countries in the world, and then turn our eyes toward ~the robots~.

Before they turn theirs toward us 👀.

Creepy.

More than half the world’s population now sits in the “global middle class,” and over two hundred million people continue to join its ranks each year. That’s more than the population of the entire US middle class, every year, joining the global middle class from some of the poorest countries on earth.

There’s a fancy economics term for what Trump is promising the tariffs can do for America, and it’s called “reshoring.” This is the inverse, of course, of “offshoring,” the process that sent those jobs out into the world in the first place.

According to the Economics Policy Institute, the globalization “of our economy… [has] eliminated more than five million U.S. manufacturing jobs and nearly 70,000 factories” from 1998 to 2021. And this — notably absent from any of the current administration’s tariff rationale — has created “often overlooked costs for Black, Brown, and other workers of color.”

Obviously this has devastated many communities in America. But these mechanisms have also greatly buoyed the incomes of those in some of the world’s poorest countries. As the economist Dani Rodrik wrote in a 2013 paper:

“The last decade has been an extraordinarily good one for developing countries and their mostly poor citizens… Their economies have expanded at unprecedented rates, resulting both in a large reduction in extreme poverty and a significant expansion of the middle class… China, India, and a small number of other Asian countries were responsible for the bulk of this superlative performance. But Latin America and Africa resumed growth as well, catching up with (and often surpassing) the growth rates they experienced during the 1950s and 1960s.”

The countries in that paragraph alone represent well over one half of the world’s population. And as entrepreneur Mark Heynen points out, over two hundred million people continue to join the ranks of the global middle class each year. That’s more than the population of the entire US middle class, every year, joining the global middle class. And the vast majority of these people live in historically low-income countries.

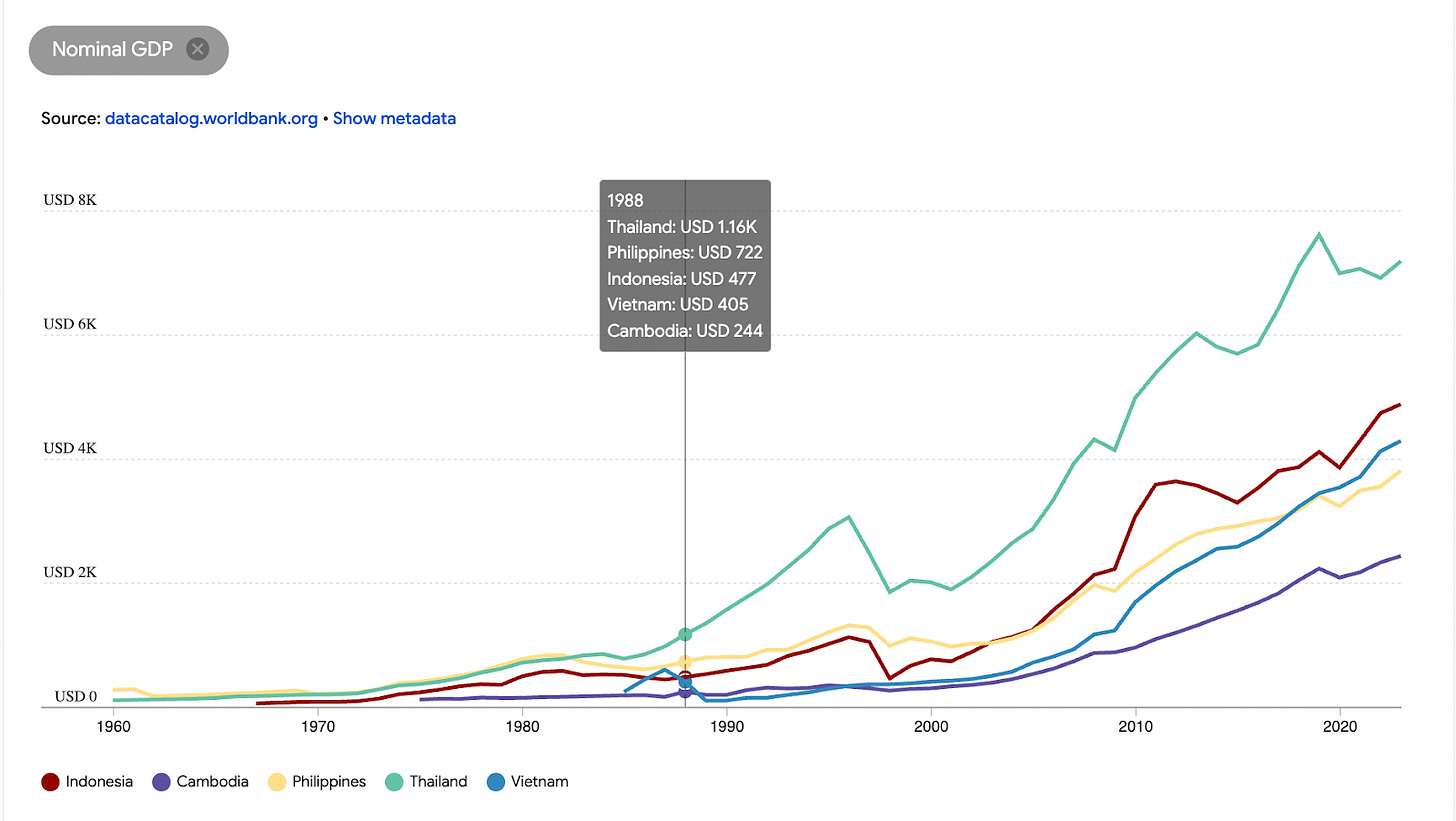

These countries don’t receive much attention in the discussion of tariffs and trade, but just see the explosive growth in the economies of a few Southeast Asia nations over the past four decades. Note how dramatically the wealth of these countries really started to take off around the late 1980’s — right as the globalization blamed for decimating the economies of many American regions took off, too.

I should make clear that, much as the current administration might try to convince us otherwise, most of these countries didn’t directly take American jobs. What’s more accurate is that globalization — including reduced trade barriers, a rise in global supply chains, and the “liberalization” of many low-income economies — helped drive both the decline of American manufacturing, and the dramatic wealth increases of the kind we can see in that chart.

It’s not just globalization and outsourcing that have wrecked American manufacturing jobs, either — among other things, economists point to the contributions of increased CEO compensation, weakened labor laws and private-sector unions, and shareholder primacy, which “focuses on maximizing the value of shareholders before considering the interests of other corporate stakeholders, such as society, the community, consumers, and employees.”

And then there’s automation.

Enter the Robots 🤖

A fun fact before we begin: the word “robot” comes from the Czech word robota, which effectively translates into “forced labor,” like the kind a serf would have had to do back when that was a thing. (I thought it meant “slave”, but seemingly not quite — but it’s splitting hairs, really. The root of robota apparently comes from the Slavic root rab though, which does mean slave.) Anyway, we can thank the Czech playwright Karel Čapek for bringing the word to us in his 1921 play, R.U.R., which stands for “Rossum’s Universal Robots.” The more you know ✨✨

There’s a world in which tariffs could lead to reshoring, which then leads to a bounty of good, high-paying manufacturing jobs like we once had in this country. But sadly, that world doesn’t seem to exist.

Shawn Fain, the president of the United Auto Workers Union, made news this week when he pointed out how absolutely fucked many Americans have been by the economy over the past several decades, and how little sympathy he has for those losing their 401k and investment savings in the stock market.

As Fain told NPR:

“We've sat here for the last 30 plus years, with the inception of [the North American Free Trade Agreement] back in 1993-94, and watched our manufacturing base in this country disappear… most working class people are trying to survive right now. And it's infuriating that our livelihoods have been stripped from us for decades and no one's cared."

He’s not wrong about that, as we saw from the Economic Policy Institute statistic above. It’s easy to see how some like Fain might be tempted to believe tariffs might click a big, global “undo” button on the last several decades of outsourcing, and bring high-paying manufacturing jobs back to the American heartland.

The problem with this argument is that there’s no big “undo” button on American manufacturing. There are many reasons for this, but a big one is that technology has improved dramatically over the past several decades. Which means in countries where labor is expensive (like the US), it’s often cheaper to employ robots in factories than it is humans. And this is especially true in the automobile industry. (Ahem, Mr. Fein.)

While robots may not (yet) have displaced many workers in low-income countries, this is only because labor there is cheap. The least expensive option for many companies may be to employ workers in low-income countries, like Vietnam and Mexico. But when forced to build products in expensive markets like the US, a great deal of research suggests these same companies will automate many of the jobs that previously employed people in low-cost markets, because it’s cheaper than hiring American workers. And so even if manufacturing plants move to the US, many of the workers hoping to find steady, high-paying jobs with them may still be screwed.

According to UNCTAD in a 2016 paper on robots and industrialization:

“The evidence also shows… that where reshoring to developed countries has occurred, it has fallen short of expected reindustrialization effects. Reshoring has mostly been accompanied by capital investment, such as in robots, with the minimal job creation that has occurred being concentrated in high-skilled activities, and has thereby sharpened income polarization.”

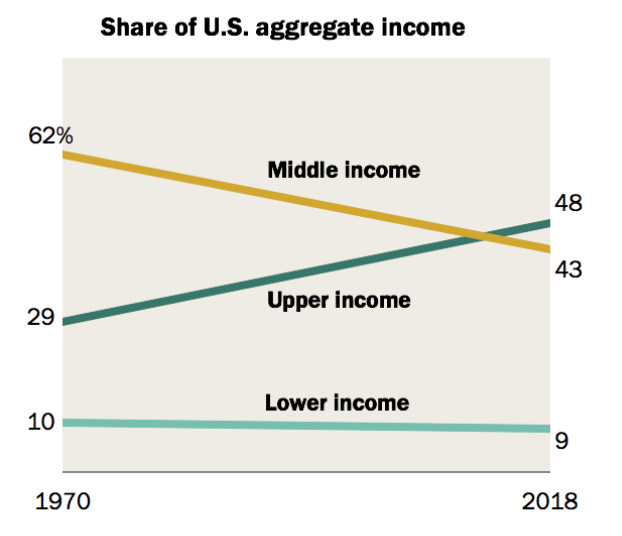

So not only does evidence point toward reshoring failing to create a bounty of new jobs, it could even increase wealth polarization in this country — which is already a huge problem. And we don’t have to look far to find evidence of a country’s rising wages leading to greater automatization:

“In response to a shrinking working-age population and rising labour costs, which have eroded the country’s cheap-labour advantage, China has embarked on a government-backed robot-driven industrial strategy entitled ‘Made in China 2025’. Each year since 2013, China has bought more industrial robots than any other country…”

And so, even as some say that years of (global!) economic hardship and tariffs will be worthwhile if it means bringing manufacturing jobs back to America, the question we must ask is not who will staff the factories, but what 🤖.

Tremendous thanks to my good friend Bianca Gay, whose Masters thesis pointed me to a lot of this research — and who also does badass work fighting online harassment in Australia. Thank you, Bianca 💪

Song of the Week: Daft Punk — Robot Rock

Find all past songs of the week & follow the playlist for updates here 🎵🎵

Yes automation, AND tarifs would need to be in the many hundreds of percent for a lot of products to become cheaper to build in the U.S. I remember the people making hard drives in Thailand when I was there made ~$8k/year.

Nice pointing out China's emphasis on automation, it's an actual long term strategy and not this B.S. macho blustering that's happening state side.

Appreciate your analysis including comparative recent history of this curious/problematic position taken by Fain! I often wonder how much Fain represents the views of the factory workers including folks who are more newly unemployed (since December Stellantis layoffs), on this subject. His position that devalues future automation as you recognize, seems a strange fantasy especially given layoffs for white-collar works related to GenAI. But it's a strange state of affairs already where a laid-off white-collar worker will proactively defend GM's Mary Barra saying she likely had nothing to do with last fall's new status quo low-respect layoff methods/manners of the legacy company, and neglecting to recognize disparity of wealth of her $29.5 million comp in a City in which at least 30 percent of folks are in real poverty. Next time I can meet someone who works in the factories, I will ask them for their sense of things. :)