Getting Physical with the Internet, Part II

Finally, with the Sharks, Subsea Cables, and Satellites — and Global Digital Divides, Green Energy, and more

This is a continuation of last week’s post (and I promise we’ll get to sharks and satellites today!) If you missed that one, I recommend starting there.

Think of these posts as a primer on the physicality of the internet, and how that physicality affects a great many things we’ll talk about in future posts, especially looking beyond the US and Europe. The largely hidden, physical bits of the internet can vastly impact internet speed and quality, data protection and privacy, online censorship and internet shutdowns, and even foreign policy and the winning of wars.

And as a housekeeping note, we’ll be taking a break next week, between Christmas and New Year, and back roaring January 4th. I’m off to Japan, Hong Kong, and India for much of January and February, where I’ll be investigating some themes for future newsletters. I’ll post some of what I find to Instagram — though be warned, the first half of January will be much more “deep powder skiing” than “internet facts” :) ⛷️

Anyway, let’s pick up where we left off last week.

A Brief Review of Size & Distance

As a reminder, we discussed how both distance and “size” (capacity) can dictate internet speed and quality. The internet is a physical thing, consisting of physical cables and exchange points, and internet content (no matter how 🔥 it is) will take longer to get from San Francisco to the Maldives than it will to Oakland, just a few miles away across the bay.

Similarly, if we think of the internet as something like a gumball machine, as I proposed last week, we can recognize how a given internet network contains finite capacity, capable of simultaneously handling a small number of large activities, like movie-watching (“large gumballs”), or many more small activities, like email-sending (“small gumballs”.)

One bonus to understanding internet provision in this very real, physical way is that many of these same principles apply to the delivery of energy to homes and businesses too. When I read about green energy today, I often see mentions of “off-peak” vs “peak” use, the distribution of energy to “the last mile,” and more. And I can rely on my background of internet knowledge to help understand it. Years ago, I met someone who worked to flatten power demand for the Bay Area’s PG&E power utility (more on this below), and was struck by how similar his energy work in California sounded to what I was researching at Google, around internet access in the Philippines.

Taken all together, we can see how certain principles around the internet’s physicality dictate certain behaviors by both individual consumers and large companies — including those providing internet and also electricity, and especially green energy, to homes and businesses.

Bandwidth vs. Bandwidth Use: a Dance 💃

For most of us, the experience of the internet over the last couple decades has been one of increasing speed. As we moved from dial-up modems to broadband in the home, and from 3G to 4G to now 5G on our phones, whatever we once struggled to do online — load a YouTube video, say (remember waiting for videos to buffer?) — now usually happens with the snap of a finger.

A more invisible shift, but one that’s true all the same, has been happening with the websites and apps we use themselves. As the internet speeds up — as the gumball dispensers get bigger in our metaphor — those making applications and websites tend to see an opportunity to make them bigger, too. They see larger gumball spouts, then rush to move the world from tiny gumballs to jawbreaker-sized behemoths.

This all works okay when we’re on the big-spout internet and using apps developed for them — but what happens when developers start making only behemoth gumballs, and internet users out in the world don’t yet have access to big gumball spouts?

Let’s look at the expansion of 5G data today. While very little on the internet now really requires a 5G mobile data connection (a behemoth gumball spout), we can see how it opens up the space for app companies, game developers, and others to think of creative ways to use this increased bandwidth. Someone with an idea for a data-intensive AI virtual friend app five years ago might have dismissed it as infeasible — but now with a bigger 5G “spout”, it might suddenly seem like a good idea.

This sets up a kind of cycle: faster internet connections beget heavier internet applications, which then come to depend on faster internet connections. What was once a text-based internet becomes a photos-based internet, and apps that used to rely primarily on photo sharing move steadily toward video.

This feels relatively seamless to many of us — at least, those of us in America, Europe, and a few other countries with cutting-edge internet technology. But for much of the rest of the world, this cycle of fast internet enabling heavy-bandwidth apps can widen digital divides where they’d begun to shrink. Brazil, the Philippines and many other countries have steadily expanded 4G internet access over the past five years, bringing many onto a level “playing field” with global internet culture. But a shift by developers in the Bay Area, Japan, and other wealthy areas to high-definition video content, the metaverse, or data-intensive AI apps — which may come to rely on the high-bandwidth 5G connections available where they’re created — can lead to many in places lacking advanced internet infrastructure falling behind again.

We All Hate Feeling Congested

Even internet and energy networks.

Another ramification of the physicality of the internet can lead to “congestion” or “peak” pricing, which can lead to all sorts of strange-seeming policies and incentives for internet and energy users. It’s worth noting, this is an area we can see really play out in the energy space, especially as communities around the world move to green energy, the supply of which can shift based on the availability of sun and wind.

Just as too many Netflix-sized large gumballs coming through the dispenser at once can slow down their delivery for everyone, too many homeowners running their washing machines at peak times can do something similar. In minor cases, this will cost the electric utility (and perhaps you) more money; but in extreme situations, it can lead to power grid failures, as sometimes happens during heat waves, or during winter 2021’s Texas power grid disaster. It’s also the reason why in some places, Netflix might load slowly in the evening — because everyone else around you with the same internet service is watching Netflix then, too.

It’s for these reasons that many power companies have smartly begun nudging users toward “off-peak” consumption — say, starting your dishwasher at night and letting it run while you sleep. This is often called “peak pricing”, and while internet companies around the world don’t do this often today, it was once common practice in many parts of the Global South, like India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and much of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Let’s imagine you’re a telecommunications company, or energy provider. You have a certain size of gumball spout — you can upgrade it eventually, but that will cost time and money. For now, you just have the one spout, and it costs you the same to maintain and run it whether a couple tiny gumballs go through, or many large ones.

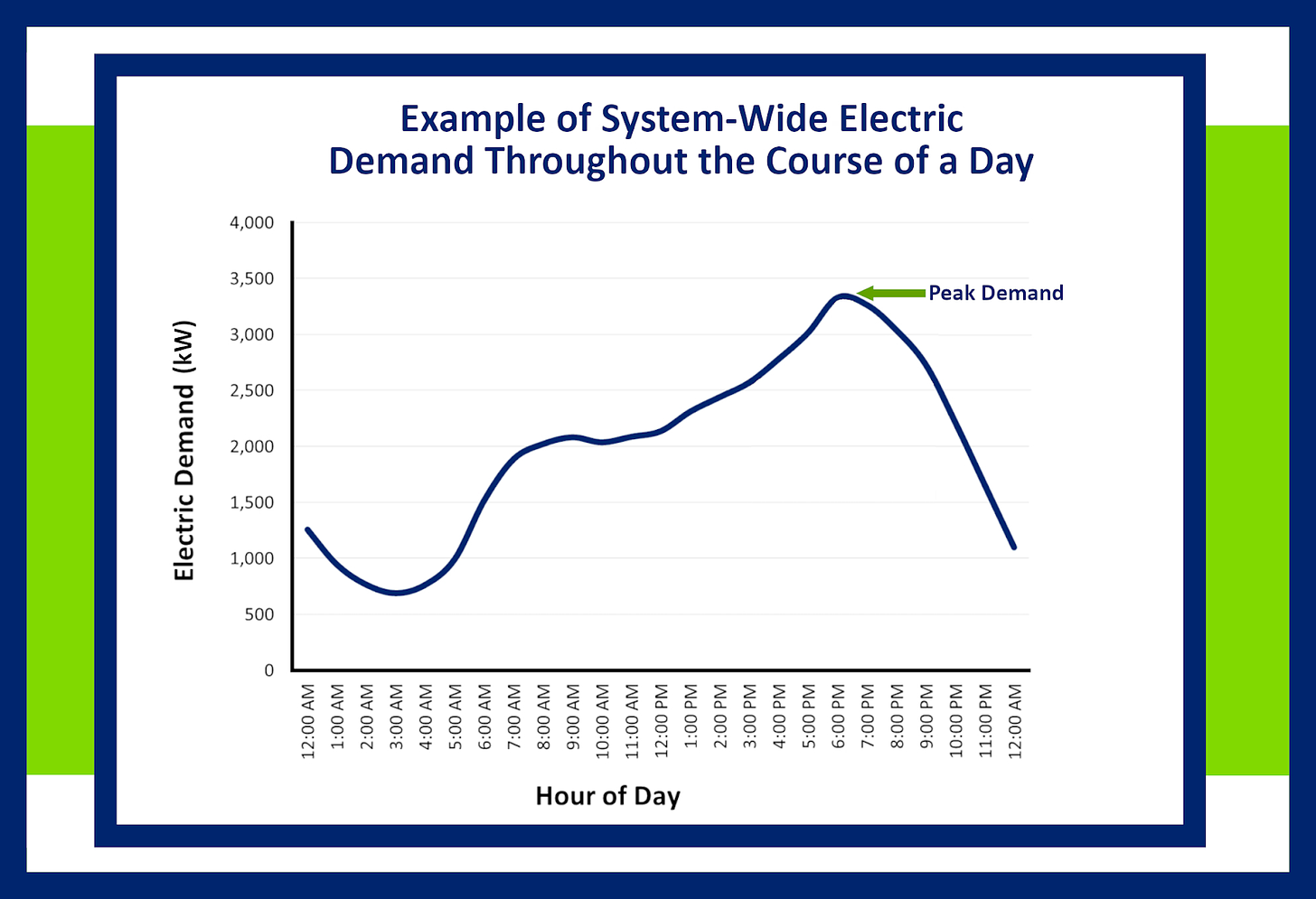

The name of the game, for both these industries, is to level demand. Here, for instance, is a graph showing energy usage by hour for Holyoke Gas and Electric:

This graph could just as easily show internet use for a home throughout the day, by the way — there’s a big dip at night while everyone sleeps, and then it picks up in the morning and stays roughly level during the day. And then usage peaks at night, when everyone’s home and on their phones and watching TV, or whatever. (Working from home since Covid began has probably changed the shape of this dramatically, but the general principle still applies.)

The problem for Holyoke Gas and Electric here is that they have to maintain a “gumball spout” large enough to deliver energy to all their customers at 5 pm — right where that Peak Demand arrow is pointing, at around 3,500 kW. But this is a waste of money; for most of the day, they’d be just fine maintaining a capacity nearly half that, around 2,000 kW!

For Holyoke Gas and Electric, and really any energy or internet supplier, their ideal situation is to nudge customers to use their services at different times of day, to flatten out demand. Which would ideally look something like, well, a flat line — in this Holyoke G&E example, centered somewhere right around 2,000 kW.

These conditions explain a number of phenomena in both the energy and internet industries, and even urban planning:

Why smart thermostats change temperatures at certain times of day to save money

Why mobile data providers in Kenya, India, and elsewhere have offered customers unlimited nighttime data

Why a need to flatten the “duck curve” of energy demand and solar / wind supply is important for the growth of green energy

Why some smart cities around the world have introduced congestion pricing for cars in downtown areas, rather than expanding the size of roads

Under the Sea 🎵

I discussed in last week’s post the challenges of accessing an internet video popular in San Francisco while on vacation in the Maldives. But we skipped over an important question: the Maldives is separated from San Francisco by over 9,000 miles of water. Even if it takes a little while, how does a video get halfway across the world on the internet without taking weeks?

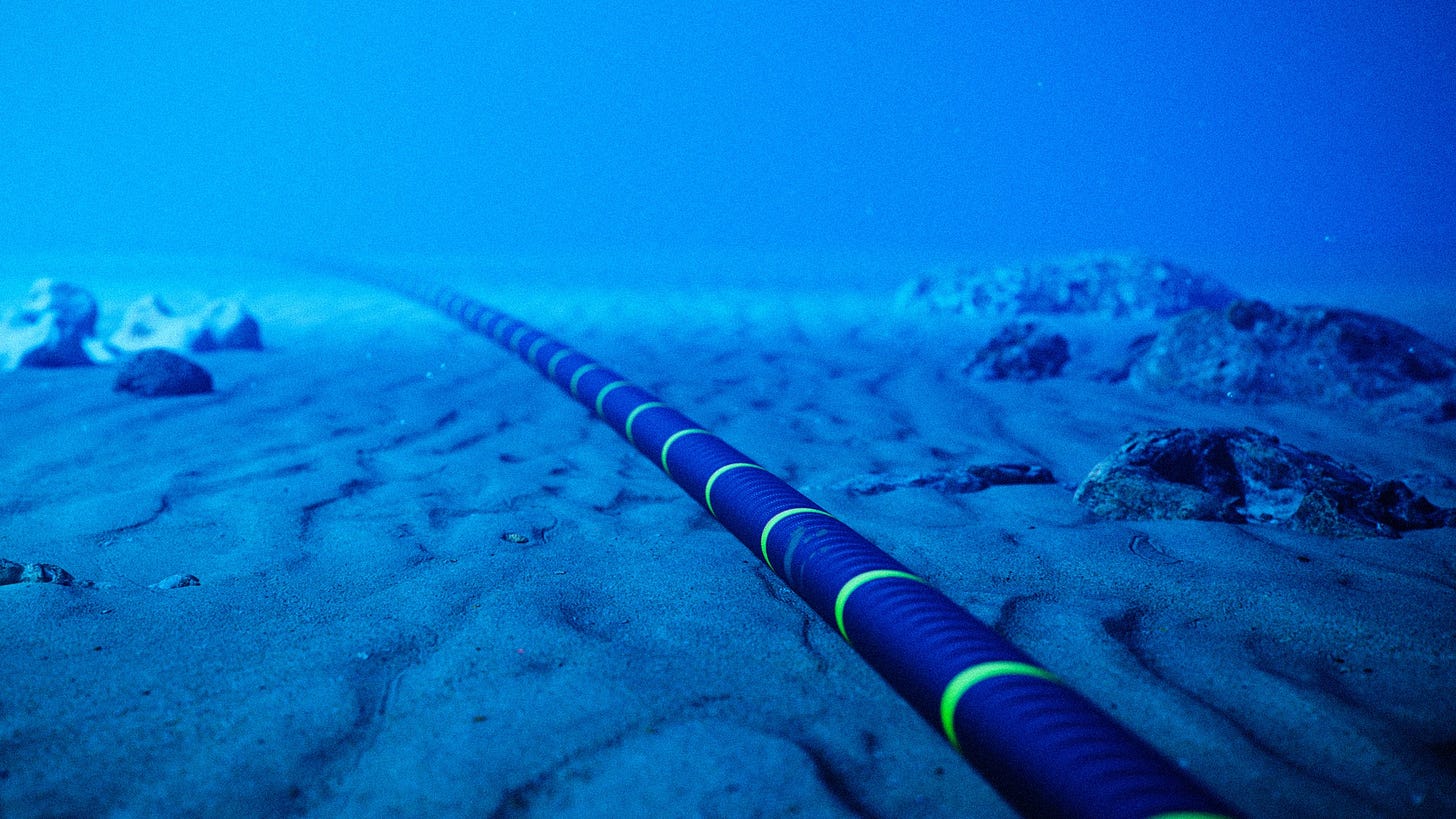

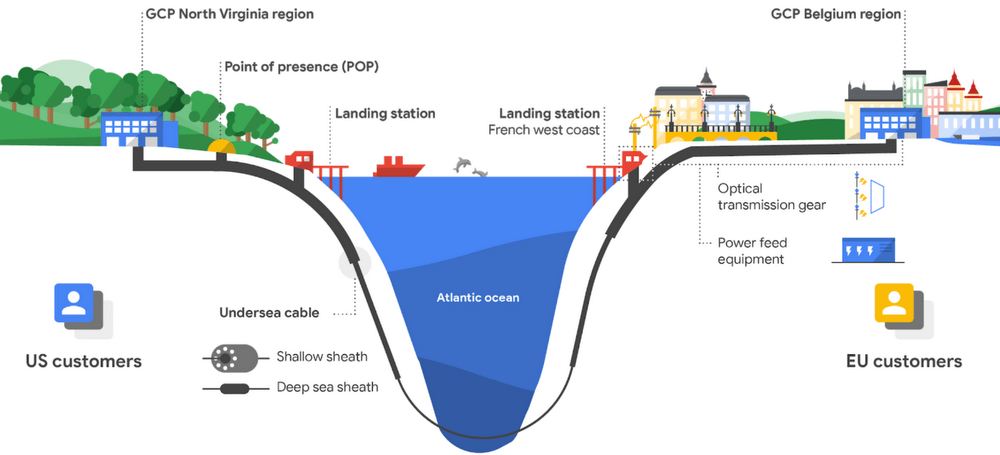

It’s not satellites (at least, not usually, yet), nor big microwave rays skipping, savior-like, across the Pacific. Instead, we have to look underwater. Governments, telecommunication companies, and even big internet companies like Google and Facebook have invested great sums of money to string internet cables across entire oceans from one continent to another. These are massive braids of thick metal and waterproof cables encompassing high-volume fiber optics strung from one shore to another by boat, and then secured in place far below the surface.

Google in 2022, for instance, launched its Equiano cable connecting mainland Europe to multiple points along the west Africa coast, before finally terminating in Cape Town. This of course doesn’t mean South Africa never had access to the internet. But now, rather than routing messages and videos through Europe, the Middle East, and then through a large number of African countries spanning the continent, that same internet content can now take a kind of undersea superhighway right to Cape Town. And then it can route through other local networks to nearby places from there.

And I think they’re very cool. Nothing, to me, demonstrates the physicality of the internet better than the landing stations where these cables touch ground.

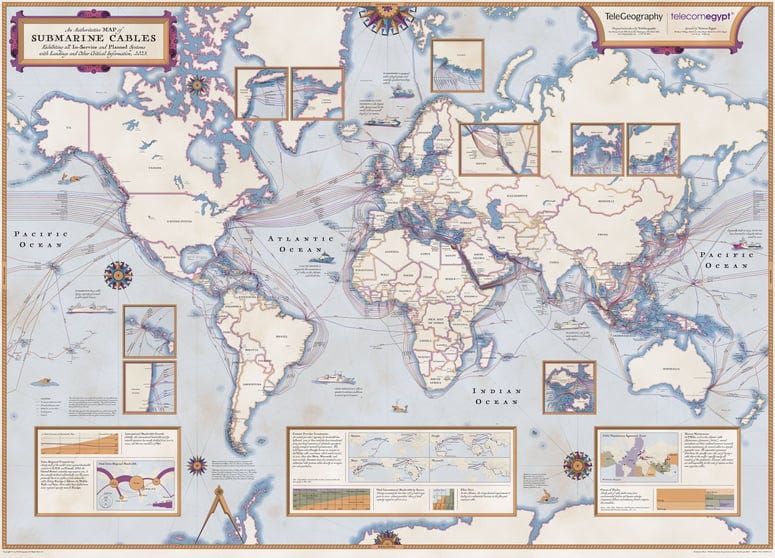

They also create really neat maps:

Subsea cables are, as I’ve hopefully shown, really, really cool. But they’re not impervious to risks. Sharks have been seen biting them (though apparently the media has, tragically for us shark lovers, overhyped this risk.) And more dangers abound: volcanoes, earthquakes, and cyberattacks have damaged cables, and either sabotage or a wayward ship anchor severed cables and cut or slowed internet access to millions in the Middle East and India in 2008. The on-land portion of a subsea cable in Egypt — it’s even shown in that fancy map above — was also cut in 2022, again temporarily cutting off internet access for millions of people.

And the deployment of subsea cables by private cables can lead to foreign policy snafus. Facebook abandoned plans in 2021 for a cable linking the US, Hong Kong and Taiwan following pressure from US national security officials. And Russia has trained dolphins to defend their military bases near Crimea (!). There hasn’t yet been evidence of dolphin sabotage on subsea cables, but it doesn’t seem that much of a stretch?

Will Satellites make all this Obsolete?

In a nutshell, no.

The general consensus is that while satellite internet — like that provided by Elon Musk’s Starlink and Amazon’s Project Kuiper — will provide valuable service in niche, hard-to-reach markets, it’s too expensive and slow to support everyone online. While remote villages, tiny islands, military outposts and other similar locations will likely benefit from satellite internet, it will be a long time before satellites compete with high-throughput land and subsea cables, if that time ever comes.

According to Business Insider:

“Brian Lavallée, a senior director at telecoms equipment supplier Ciena, said satellite internet networks and undersea cables were "highly complementary" and not intended to compete against each other. ‘Think of satellite networks as on-ramps to highways with the highways being the submarine networks," he told Insider. "For small islands with no submarine cables, satellite networks are a viable, or sometimes the only, alternative… Satellite internet access is not likely to overtake undersea cable infrastructure in our lifetime, primarily because they're not intended to compete.’”

I’ll do a whole post on this sometime in the future — I was, after all, very involved in numerous Google projects aiming to connect the “next billion” internet users in remote, low-income regions, and I personally believe there’s good reason nearly all of these eventually tapered off. And Google wasn’t the only one pursuing these moonshot internet access projects, either.

And just like subsea cables, the way in which satellites can be deployed (or turned off) to a region independent of local government permission raises lots of foreign policy hackles. China is apparently fearful of Starlink and other satellite internet companies providing internet to certain areas they might like to control (e.g. Taiwan), and have recently begun testing their own satellite internet system. And Elon Musk notedly received heat from the Pentagon this fall for refusing to use Starlink to support Ukraine in Crimea. He also (again — quite the strong boy these days!) said Starlink would provide connectivity to assist aid groups in Gaza this October.

It’s the Control, Stupid!

With apologies for a silly appropriation of the James Carville quote, I’d like to make one last point about the physicality of the internet: it often boils down to control, and government control in particular. Many of the recent controversies arising from satellite and subsea cable internet circle around who gets to control the internet — China, for instance, doesn’t much seem to like it when foreign powers, whether they be Facebook, Elon Musk, or the US government, overstep what they see as boundaries to around internet access to Hong Kong and Taiwan. This ties into our discussion of the internet in Cuba, too. Unsurprisingly, certain countries that like controlling what their citizens see, hear and do don’t exactly love when foreign powers pledge to bring fast internet to their citizens.

I’ll save this for a future post, but suffice to say now the internet’s physicality also allows certain other types of control, including data residency laws mandating whether citizens’ data must be stored on servers within a country’s borders. And China and a number of other countries — many of them heavily authoritarian — have recently pushed for the idea of “cyber-sovereignty,” whereby individual countries could be allowed to maintain their own local internets, and control (and censor) them how they please, much as China does today.

But that’s all for this week! Thanks for sticking around for the last post of inaugural year of this newsletter, and have a great rest of 2023 — see you in the new year 🥳🥳.

Song of the Week: Big Thief — Shark Smile